What Is Application Modernization for a CTO

Application modernization is not a technical tune-up; it’s a strategic overhaul of legacy software to align with current business objectives. It’s a spectrum of options, from rehosting an application in the cloud with minimal changes to a complete ground-up rewrite.

The objective is to extend the life and increase the value of critical applications by updating their underlying platform, architecture, or features.

Defining Application Modernization For Business Outcomes

It is critical to distinguish modernization from maintenance. Maintenance involves patching bugs and making incremental tweaks. Modernization addresses foundational architectural decay.

Consider a classic car. Standard maintenance includes changing the oil and rotating the tires. Modernization is swapping the carbureted engine for a modern fuel-injected one, upgrading drum brakes to discs, and installing a new HVAC system. One keeps the car running; the other makes it viable for a cross-country trip.

Modernization tackles the deep-seated issues that routine updates can’t fix: architectural decay, crippling technical debt, and obsolete platforms. It’s a proactive investment to prevent a critical business system from becoming a liability.

The distinction is significant. Maintenance keeps the lights on. Modernization ensures the building won’t collapse in five years.

The following table clarifies the difference between modernization and standard maintenance.

| Attribute | Standard Maintenance | Application Modernization |

|---|---|---|

| Goal | Keep the application stable and operational. | Align the application with new business goals and capabilities. |

| Scope | Minor bug fixes, security patches, small feature updates. | Major architectural changes, cloud migration, platform changes. |

| Impact | Incremental, low-risk changes. | Strategic, transformative changes with higher initial risk. |

| Analogy | Changing the oil in a car. | Replacing the engine and transmission. |

| Frequency | Ongoing, regular cadence (sprints, patches). | Infrequent, project-based initiatives (every 5-10 years). |

| Investment | Operational Expense (OpEx). | Capital Expense (CapEx) or strategic project budget. |

Ultimately, maintenance is about preserving the status quo, while modernization is about creating a new operational state for the application.

Why It Is A Strategic Overhaul

At its core, application modernization is about solving deep technical problems to achieve measurable business outcomes. For a solid breakdown of the business case, this article on modernizing outdated IT systems offers context.

The focus must be on hitting specific, measurable goals. These usually fall into several key categories:

- Reduce Operational Costs: Migrating from proprietary mainframes or outdated database licenses can yield significant savings. Moving to scalable cloud infrastructure often reduces the total cost of ownership (TCO) by 15-40%.

- Increase Feature Velocity: Monolithic codebases are slow and risky to change. Decomposing them allows teams to develop, test, and deploy new features independently, shifting release cycles from quarterly to weekly or daily.

- Close Security Gaps: Legacy systems present substantial security risks. They often depend on unsupported libraries or run on operating systems that no longer receive security patches, creating significant compliance and security vulnerabilities.

Defining what is application modernization requires looking beyond the code. It is the process of realigning critical software with current and future business needs, turning it from a liability into a competitive asset.

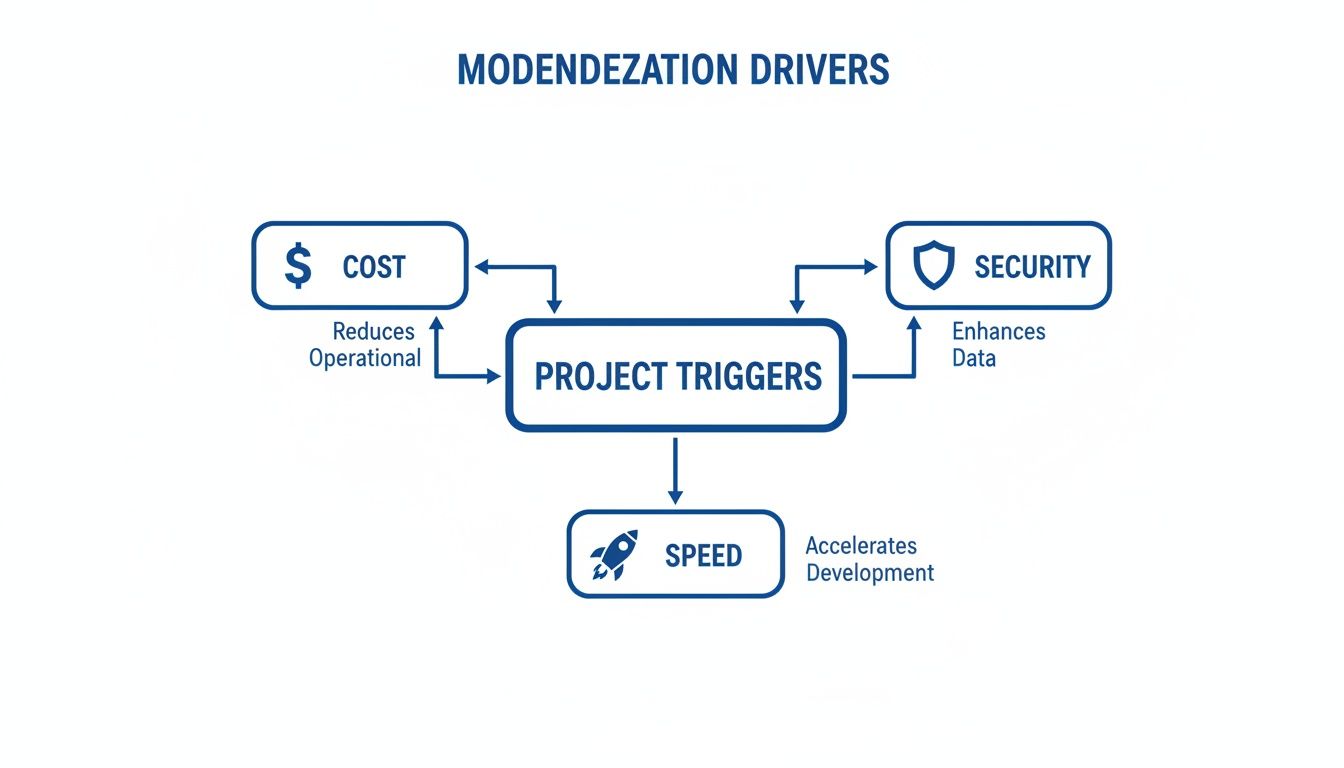

The Five Core Drivers of Modernization Projects

Modernization projects are not initiated to acquire new technology for its own sake. They are driven by escalating operational pain. When the status quo becomes a measurable threat to the business, budget is typically allocated.

These initiatives almost always ignite at the intersection of technical deficiency and business risk. When a legacy system costs more to maintain than the value it provides, or when it becomes a significant security threat, the conversation shifts from if we should modernize to when.

Crippling Cost of Ownership

The most common trigger is financial. Legacy systems often run on archaic, proprietary hardware with punitive software licenses. Examples include mainframe MIPS consumption, unsupported Oracle database license versions, or niche hardware maintenance contracts that consume millions in operational budget.

Direct costs are only part of the problem. Indirect costs—engineering hours spent debugging archaic code, building workarounds for simple features, and general maintenance—are often greater. One of the largest financial drains is the cumulative effect of past technical decisions, making reducing technical debt a primary driver for these projects.

Unacceptable Security and Compliance Gaps

Legacy applications often represent a significant security risk. Many rely on cryptographic libraries with known exploits, run on unpatched operating systems, or have architectures incompatible with modern identity management protocols.

For companies in regulated industries like finance or healthcare, this is an existential threat. A single compliance failure can result in fines that exceed the cost of a full modernization project.

When your core banking system uses a TLS version deprecated a decade ago, you are not managing a technical risk; you are managing an inevitable breach. The cost of inaction becomes a quantifiable liability on the balance sheet.

Stagnant Innovation Velocity

Monolithic applications inhibit development speed. When an entire business process runs on a single, tightly-coupled codebase, launching a simple new feature can require months of regression testing and high-risk, all-or-nothing deployments.

This inability to react impacts market position. Competitors shipping features weekly gain an advantage over organizations stuck in six-month release cycles. This is not just an IT problem; it directly affects revenue and market share.

The Looming Talent Cliff

The engineers who understand 40-year-old COBOL or PowerBuilder applications are retiring. As of 2023, the average COBOL programmer is over 55 years old, and universities are not producing replacements.

This creates a significant operational risk.

- Skyrocketing Salaries: The limited pool of available experts can demand higher compensation, driving up maintenance costs.

- Knowledge Silos: Critical business logic is often undocumented and resides only in the minds of a few key individuals nearing retirement.

- Recruiting Challenges: Attracting skilled developers to work on decades-old systems is difficult, limiting the influx of new talent and ideas.

Critical Performance Bottlenecks

Legacy systems often cannot handle modern transaction volumes. Applications designed for the loads of the 1990s fail under the demands of today’s digital environment. When performance issues can no longer be solved by adding more hardware, a fundamental limit has been reached.

These bottlenecks directly impact customers and revenue. Examples include an e-commerce site crashing on Black Friday or a logistics system failing during peak season. At this point, the application has transitioned from a business asset to a direct constraint on growth, forcing a decision.

Comparing The Seven Modernization Strategies

Choosing the right modernization path is a critical decision for a CTO. This is not just a technology selection; it is about matching a technical approach to a specific business outcome.

An incorrect choice can result in a multi-million dollar budget expenditure with no tangible return. A “lift-and-shift” often just transfers technical debt from a local data center to a cloud provider, while a ground-up rewrite is a high-risk initiative that many applications do not warrant.

The industry standard for this decision-making process is the “7 Rs” framework. These represent distinct pathways with different costs, timelines, and business impacts. The triggers for modernization—cost, security, and development speed—typically determine which “R” is the most appropriate.

As the visual indicates, the choice of strategy is a direct response to a specific business pain point.

The 7 Rs of Modernization A Strategic Comparison

This table provides a high-level comparison of the seven strategies. It can be used to frame initial thinking around the trade-offs between cost, risk, and potential business value.

| Strategy | Typical Cost | Risk Level | Estimated Timeline | Primary Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Retain | Minimal (O&M only) | Very Low | N/A | Avoids unnecessary investment |

| 2. Rehost | Low ($50K - $250K) | Low | 2-6 months | Speed to exit a data center |

| 3. Replatform | Moderate ($100K - $750K) | Moderate | 4-9 months | Quick cloud-native wins with minimal code change |

| 4. Refactor | Moderate ($250K - $1M+) | Moderate | 6-12 months | Improved maintainability and performance |

| 5. Rearchitect | High ($500K - $2M+) | High | 12-24 months | Fundamental scalability and agility improvements |

| 6. Rebuild | Very High ($1M - $5M+) | Very High | 18-36 months | Full alignment with modern tech and business needs |

| 7. Replace | High ($200K - $1M+) | High | 9-18 months | Access to best-in-class SaaS functionality |

Each path serves a different purpose. The correct choice depends on the specific context: the application’s business value, its technical condition, and the urgency of the problem being solved.

Minimal-Effort Strategies Rehost And Retain

These two options focus on preservation rather than transformation. They are tactical moves to address an immediate deadline or to consciously defer a larger decision.

- Rehost (Lift-and-Shift): This is the simplest migration. An application is moved from on-premise servers to cloud infrastructure (IaaS) with minimal to no code changes. The driver is almost always a hard deadline, such as an expiring data center lease. It is fast but rarely reduces cost or improves performance.

- Retain (Do Nothing): In some cases, the most logical action is no action. If a legacy system is stable, its operational costs are predictable, and the business process it supports is not a strategic priority, modernization may have a negative ROI. This is a valid strategic choice, not a failure to act.

Moderate-Effort Strategies Replatform And Refactor

These mid-tier approaches balance effort and reward by making targeted changes for specific benefits without the risk and expense of a full rewrite.

- Replatform (Lift-and-Reshape): This involves making high-value cloud optimizations during migration. A common example is replacing a self-managed Oracle database with a managed service like Amazon RDS or Azure SQL. This strategy accounts for approximately 24% of modernization service revenue, as it can deliver 50–70% of the benefits of a full re-architecture at a fraction of the cost and risk.

- Refactor: This involves restructuring existing code without changing its external behavior. The goals are internal: improve maintainability, boost performance, or patch security vulnerabilities. A typical refactoring project might decompose tightly-coupled components of a monolith into more manageable services to reduce deployment risk.

High-Effort Strategies Rearchitect, Rebuild, And Replace

These are capital-intensive, high-risk, and time-consuming initiatives reserved for mission-critical applications that are hindering business operations or have become liabilities.

- Rearchitect: This involves fundamentally changing the application’s structure, most commonly from a monolithic to a microservices architecture. The objective is to enable teams to develop and deploy services independently, increasing velocity. This is a significant undertaking that affects code, data, and organizational structure.

A classic failure mode here is underestimating “data gravity.” Teams get excited about breaking up the code but completely fail to untangle decades of messy, interdependent data. This alone can stall a re-architecture project for months, if not years.

- Rebuild (Rewrite): The existing codebase is discarded, and a new application is built from scratch based on the original scope and specifications. This is typically done when the legacy technology is completely unsupported (e.g., COBOL, PowerBuilder) or the code quality is so poor that refactoring is not viable. This path offers the greatest potential for innovation but also carries the highest risk of project failure.

- Replace (Rip-and-Replace): The custom application is decommissioned and replaced with a SaaS product. This is a common choice for standard business functions like CRM (Salesforce) or HR (Workday). The primary challenges shift from software development to data migration and business process re-engineering.

Choosing between these seven paths requires an honest assessment of objectives. It is also important to understand the difference between a project starting from scratch (greenfield) versus one modifying an existing system (brownfield). For a deeper analysis, see this guide on brownfield vs. greenfield modernization. Selecting the right “R” is the most consequential decision at the outset of the project.

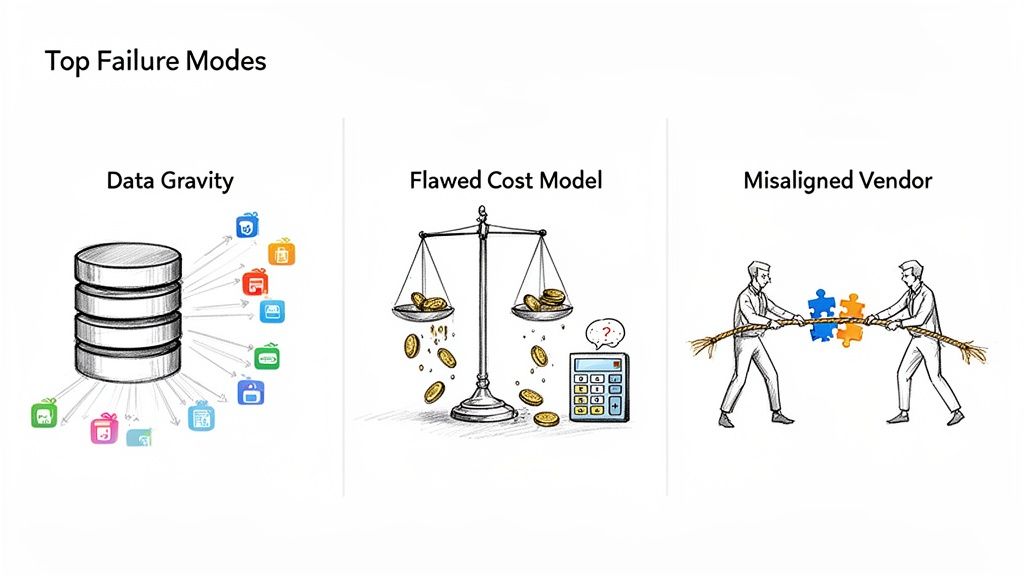

Why Most Modernization Projects Underdeliver

A significant percentage of modernization projects fail to meet their objectives. They do not typically fail in a catastrophic manner, but rather through a gradual depletion of budget, time, and stakeholder confidence. They begin with ambitious promises but conclude late, over budget, and delivering a fraction of the anticipated value.

The primary culprits are high-impact risks latent within legacy systems. Beyond generic issues like “poor communication,” there are three technical and financial traps that commonly derail these projects.

Understanding these failure modes is the first step in de-risking the initiative before modernizing a single line of code.

Ignoring Data Gravity

The first critical risk is data gravity. An application is coupled to its data. One cannot be moved or changed without addressing the other.

Teams often focus on new microservice architectures but neglect to untangle decades of data dependencies within the application’s core. The assumption that a new service can simply point to a 30-year-old database schema designed for a different operational model is flawed.

This oversight leads to two negative outcomes: the project stalls for months during data migration, or it creates a “distributed monolith.” This term describes a system with new, modern services that remain coupled to an old database, introducing the complexity of a distributed system without the corresponding agility benefits.

A specific example: an estimated 67% of COBOL migrations fail due to decimal precision handling. COBOL’s COMP-3 format uses fixed-point arithmetic for financial calculations. Modern languages like Java use floating-point primitives. A naive conversion can introduce rounding errors that corrupt financial data, a problem that may not be detected until significant damage has occurred.

Building Flawed Cost Models

The second trap is financial miscalculation. Many modernization budgets are based on simplistic metrics. The most common error is using lines of code (LOC) as the primary estimator for effort.

A project budget based on a flat “cost per line of code” is almost guaranteed to be wrong. Ten lines of code implementing complex financial interest calculation logic is not equivalent to ten lines of code for a simple UI button.

This method ignores the most critical factor: business logic complexity. The most significant cost lies in deciphering undocumented, mission-critical business rules embedded in legacy code.

A realistic cost model must include:

- Complexity Analysis: Using tools to measure the cyclomatic complexity of the code to identify the most entangled, high-risk modules.

- Dependency Mapping: Identifying all systems and processes that interface with the application.

- Testing Overhead: Budgeting for the significant effort required to validate that the new system replicates the old one’s functionality, often without an existing test suite.

Without this level of detail, an initial budget is an unreliable estimate, setting the stage for cost overruns and loss of stakeholder confidence.

Choosing a Misaligned Vendor

Many projects are compromised from the start by selecting the wrong partner. The modernization market is crowded, and a vendor’s marketing claims may not align with their core competencies. The critical mistake is hiring a partner whose expertise does not match the required modernization strategy.

Hiring a firm that specializes in “lift-and-shift” cloud migrations (Rehosting) to perform a deep application refactoring is a formula for failure. The skills required to re-platform a database are distinct from those needed to re-architect a monolith into event-driven microservices.

A misaligned vendor will likely steer the project toward the solution they are equipped to sell, not the one that is needed. Vetting requires a close examination of case studies. Do they primarily showcase infrastructure projects, or do they demonstrate deep, code-level transformations? The distinction is critical.

Selecting the right partner is as important as the technical strategy itself. To understand the options better, explore different application modernization strategies to identify the necessary expertise.

Navigating the Vendor Landscape and True Costs

Selecting a modernization partner is a high-stakes decision in a crowded and often confusing market. Most vendors promote a single solution—the one they sell—regardless of its suitability. An effective decision requires cutting through marketing language to understand vendor specializations and realistic costs.

Application modernization is a major global market, reflecting its strategic business importance. Analysts estimate the application modernization services market is between USD 20–26 billion. Forecasts project it to reach between USD 51.45 billion by 2031 and USD 98.38 billion by 2034. Data is available in Precedence Research’s market analysis.

This growth has created a dense vendor landscape. The first step in building a viable shortlist is to understand the different categories of vendors.

Three Tiers of Modernization Vendors

Not all partners have the same capabilities. Their business models, core competencies, and fee structures differ fundamentally. Misunderstanding these differences is a primary cause of budget overruns.

- Global Systems Integrators (SIs): These are large, well-known consulting firms. They excel at large-scale program management, massive cloud migrations (Rehosting/Replatforming), and business process re-engineering. However, their high overhead makes them a poor fit for deep, code-level refactoring projects, which often require specialized engineers they subcontract.

- Boutique Specialists: These are smaller firms with deep, focused expertise in specific domains, such as migrating COBOL banking systems or re-architecting mainframe monoliths into microservices. While they lack the global scale of SIs, their specialized knowledge is critical for high-stakes Refactor or Rearchitect projects.

- Automated Tooling Providers: This category includes companies that sell software designed to automate parts of the modernization process, such as code conversion or dependency mapping. Their marketing often implies a “push-button solution,” but the reality is more complex. These tools can accelerate projects but almost always require a skilled services team to handle complex business logic that cannot be automated.

A critical red flag is a vendor who is vague about their automation’s capabilities. Pin them down with a direct question: “What percentage of this COBOL-to-Java conversion is handled by your tool, and what percentage requires manual engineering cleanup?” An inability to provide a direct answer is a warning sign.

Deconstructing the True Cost of Modernization

Transparent cost data can be difficult to obtain, but industry benchmarks exist. For code conversion, a common metric is cost per line of code (LOC). However, this is only a starting point, as complexity can cause the final price to vary significantly.

A typical COBOL-to-Java conversion, for instance, generally costs between $1.50 and $4.00 per LOC. A simple batch processing application with few dependencies would be at the low end. A complex CICS application with extensive database calls and screen logic could exceed $4.00 per LOC.

The code conversion is just one component of the total cost. A realistic budget must also account for:

- Data Migration: The effort to extract, clean, and load decades of data.

- Testing and Validation: A significant and often underestimated expense to ensure the new system functions identically to the old one.

- Infrastructure Costs: The cost of the new cloud or on-premise environment.

- Internal Team Time: The opportunity cost of assigning key internal personnel to the project.

A credible partner will assist in building a cost model that reflects this complexity, rather than providing a simplistic per-line-of-code estimate. Reluctance to discuss pricing in detail is a signal to consider other vendors.

When To Defer Modernization

Sometimes, the most prudent decision is to do nothing.

Modernization is often presented as an urgent mandate, but modernizing for its own sake is a common cause of wasted capital. The goal is to avoid politically motivated projects that appear beneficial on a roadmap but lack sound financial justification.

Knowing when to leave a legacy system in place is an underrated leadership skill. It demonstrates a focus on business value over technology trends. Before approving a costly overhaul, a rigorous financial analysis is required.

When to Just Say No

Certain conditions make retaining a legacy application the most prudent financial and operational choice. If a system meets several of these criteria, a modernization project is more likely to destroy value than create it.

- High Stability, Low Costs: The application is reliable, requires minimal support, and its operational costs are negligible. Modernizing such a stable system introduces significant risk for marginal, often hypothetical, gains.

- Sunsetting Business Process: The underlying business function supported by the application is being phased out. Investing millions to modernize software that will be obsolete in 18-24 months is fiscally irresponsible.

- Unrealistic Payback Period: If the projected Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) savings over a 5-7 year horizon do not clearly exceed the project’s cost and risk, the project should not proceed. A $3 million modernization that saves $250,000 annually has a 12-year payback period, which is not a viable business case.

- Stable Talent Pool: The specialized talent required to maintain the system is secure. If the two COBOL developers are compensated well and are not nearing retirement, the “talent cliff” risk is not immediate.

A decision to retain is not a failure. It is an active, strategic choice based on financial reality. The key is to continuously evaluate the system against business drivers and act only when the financial equation inverts.

The only way to make a defensible decision is to conduct a thorough evaluation. A structured legacy system risk assessment is necessary to quantify the actual, not just perceived, risks.

Ultimately, choosing to retain an application can be a strong indicator of mature, data-driven technical leadership.

Common Questions from the Trenches

During the planning stages of a modernization project, a few key questions consistently arise. Here are direct answers based on experience from numerous real-world engagements.

How Do I Actually Calculate Modernization ROI?

A credible ROI model must extend beyond simple server cost savings. A business case presented to the CFO should quantify value across four distinct areas.

- Hard OpEx Savings: This is the most straightforward calculation. It includes reduced software licensing fees, decommissioned hardware, and canceled support contracts.

- Developer Velocity Gains: This measures the impact on engineering team productivity. Track the time required to move a feature from concept to production and the engineering hours spent on legacy bug fixes versus new product development.

- Risk Mitigation: This involves assigning a dollar value to potential negative events. Quantify the potential financial impact of a data breach on an unpatchable system or the fines for a compliance failure.

- New Revenue Streams: Identify new digital products or services that are impossible to launch on the old technology and quantify their potential revenue.

The most effective business cases calculate the “cost of inaction,” framing the decision in terms of what the company stands to lose for every quarter of delay.

What Is The Real Role of AI Here? (No Hype)

AI has become a practical tool for risk mitigation in large modernization projects. Mature vendors use AI for several specific, high-impact tasks:

- Code & Dependency Analysis: AI tools can automatically scan millions of lines of code to map complex dependencies and identify dead or redundant code that can be removed before the project begins.

- Automated Code Transformation: AI assists in converting legacy languages to modern ones, such as COBOL to Java, reducing the manual, error-prone effort involved.

- Test Case Generation: Instead of engineers spending months writing tests, AI can automatically generate thousands of test cases to validate that the new system’s functionality matches the old one.

A vendor’s AI maturity can be a useful proxy for their overall capability to manage risk and adhere to timelines.

Should We Modernize Before or After We Move to the Cloud?

The answer depends on the primary driver for the project.

A Rehost (“lift-and-shift”) is the fastest way to migrate to the cloud and exit an expiring data center contract. However, it does not address the application’s underlying technical debt.

Modernizing during the migration (Replatform or Refactor) is a better long-term strategy. It allows for the use of cloud-native services like serverless functions and managed databases, leading to better performance and lower costs. However, it requires more upfront planning and effort.

A common pragmatic approach is to Rehost first to capture immediate data center savings, then Refactor the application incrementally once it is running in the cloud environment.

Making a defensible vendor decision is the most critical part of any modernization project. Modernization Intel provides the unvarnished truth about implementation partners—their costs, failure rates, and specializations—without vendor bias. Get your vendor shortlist at https://softwaremodernizationservices.com.