A Practical Guide to the Technical Debt Calculation Formula

When engineering teams discuss technical debt, finance departments often hear a vague complaint, not a quantifiable business risk. The conversation stalls because “messy code” doesn’t have a line item in the budget.

This isn’t an engineering problem; it’s a communication failure. To secure investment for remediation, you must translate technical issues into financial terms.

Why Most Technical Debt Discussions Fail

Leaders generally understand that technical debt exists, but without a specific cost attached, it remains an abstract concept that is consistently deprioritized in favor of new features.

The key is to shift the conversation from code quality to financial impact. Frame it as a loan. The “principal” is the one-time cost to remediate existing shortcuts and suboptimal code. The “interest” is the recurring productivity loss—slower feature delivery, increased bug-fix cycles, and developer friction—that silently drains the budget.

Our analysis of 52 enterprise codebases (200K-2.5M LOC) found:

- Median annual “interest” cost: $1.8M in lost productivity (based on fully-loaded engineer cost × velocity reduction)

- Technical Debt Ratio range: 3.2% (well-maintained) to 47.8% (legacy monoliths)

- Velocity impact: Teams with TDR >25% delivered 62% fewer story points per sprint than teams with TDR <10%

- Incident correlation: Each 10% increase in TDR correlated with +34% production incidents

Real example: 680K LOC fintech codebase with 38% TDR. Estimated remediation: $2.4M (principal). Measured annual drag: $3.1M in lost velocity + incidents. Payback period: 9.3 months.

Shifting from “our code is difficult to work with” to “our current technical debt is costing us an estimated $3.1 million per year” forces a different kind of discussion. This requires a standardized calculation method.

From Vague Feelings to Hard Numbers

The simplest and most effective starting point for business-level communication is the Technical Debt Ratio (TDR).

Technical Debt Ratio (TDR) = (Remediation Cost / Development Cost) × 100

This formula directly compares the cost of fixing existing problems (Remediation Cost) to the initial investment required to build the software (Development Cost). A high TDR indicates that a significant portion of the initial capital investment is encumbered by future rework.

A TDR of 25% means that for every dollar spent on initial development, an additional 25 cents is now required for remediation. This frames the issue not as an engineering complaint but as an objective business risk, providing the data needed to justify investment in refactoring or specific application modernization strategies.

The Cost of Inaction is a Measurable Disadvantage

Choosing not to formally measure technical debt is a strategic decision to accept a competitive handicap. As system complexity grows, the “interest payments” manifest as development slowdowns and maintenance overhead, directly impeding innovation velocity.

This is a measurable outcome. Gartner predicts that by 2025, organizations that formally track and manage their TDR will deliver new functionality 35% faster than competitors who do not. A consistent calculation method serves as the bridge between engineering realities and executive decision-making, enabling strategic resource allocation.

Key Technical Debt Formulas at a Glance

While TDR is effective for high-level business discussions, other formulas provide deeper, more granular insights for engineering teams. Each method serves a different purpose and relies on specific data inputs, from cost estimates to static code analysis.

| Formula / Method | Calculation | Primary Use Case | Required Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical Debt Ratio (TDR) | (Remediation Cost / Development Cost) x 100 | High-level business communication; quantifies debt relative to initial investment. | Total development cost; Estimated cost to fix all issues. |

| SQALE Method | Sum of remediation costs for all identified code violations based on a quality model. | Granular, code-level analysis for prioritizing fixes within engineering teams. | Static analysis tool (e.g., SonarQube); Defined remediation costs per issue type. |

| Code Scene (Hotspots) | Analysis of files with high complexity and high change frequency (churn). | Identifies high-risk “hotspot” files that are frequent sources of bugs and maintenance effort. | Version control history (Git); Code complexity metrics (e.g., Cyclomatic Complexity). |

| Maintainability Index (MI) | Formula based on Halstead Volume, Cyclomatic Complexity, and Lines of Code (LOC). | Quick assessment of overall code health; identifies modules that are difficult to maintain. | Lines of Code (LOC); Cyclomatic Complexity; Halstead metrics. |

Understanding these different methods allows you to select the appropriate tool for a given audience. TDR is for the CFO, SQALE is for the engineering manager, and hotspot analysis helps identify the most immediate risks in the codebase.

The Four Essential Debt Calculation Formulas

Attempting to quantify technical debt without a formula is like navigating without GPS—you are moving, but your position and deviation from the optimal path are unknown. While numerous models exist, most are derived from four foundational methods.

These should be viewed not as competing options but as a toolkit of analytical lenses. One is suited for a budget presentation to the CFO, while another provides the granularity needed for sprint planning. The objective is to apply the right formula for the task.

This diagram illustrates the core concept every formula attempts to measure: the financial gap between the initial cost of rapid development and the higher future cost of remediating the resulting shortcuts.

Technical Debt Ratio (TDR)

For communicating with business stakeholders, the Technical Debt Ratio (TDR) is the primary metric. It frames the problem in financial terms by comparing the cost to fix the issues with the cost to create them.

- The Formula:

(Remediation Cost / Development Cost) x 100 - Why it’s Effective: A TDR of 25% requires minimal technical translation. It communicates to a CFO that for every dollar of initial development expenditure, the organization has accrued twenty-five cents of remediation liability. It is a direct input for financial planning.

- Its Limitation: TDR is a high-level indicator. It quantifies the magnitude of the problem but provides no information about the location or nature of the debt (e.g., security vulnerability vs. poor maintainability).

The SQALE Method

The SQALE (Software Quality Assessment based on Lifecycle Expectations) method provides a more granular analysis. It estimates remediation effort in units of time—typically person-days—and categorizes it by quality characteristics.

SQALE assesses factors like reliability, security, maintainability, and changeability. Static analysis tools leverage this method to generate a structured remediation backlog.

Instead of a general statement like “we have debt,” this method produces specific findings, such as “we have 15 person-days of remediation work to address security issues and 30 person-days to improve maintainability.” This data can be directly integrated into sprint planning.

Code-Based Remediation Cost

This is the most direct, bottom-up approach, implemented by tools like SonarQube. It scans a codebase against a predefined set of rules and assigns a specific time-based cost to fix each violation. A complex method might be assigned a 30-minute remediation time.

The total debt is the sum of these individual time estimates. The output is a concrete figure, such as “4,200 hours of remediation effort,” which can be converted to a dollar amount by multiplying it by the team’s average loaded hourly cost.

- Why it’s Effective: It is highly specific and actionable for developers, providing a prioritized list of issues with time-to-fix estimates.

- Its Limitation: This method excels at identifying code-level issues (“code smells”) but typically fails to detect systemic architectural or design flaws that are not captured by individual rules.

Maintainability Index (MI)

The Maintainability Index (MI) provides a single score, typically from 0 to 100, that represents the overall health of a codebase or module.

The original Hewlett-Packard formula combines several metrics:

- Halstead Volume: A measure of program vocabulary and length.

- Cyclomatic Complexity: The number of linearly independent paths through a code block.

- Lines of Code (LOC): A measure of size.

A high MI score indicates that the code is relatively easy to understand, modify, and test. A low score signals a module with high entropy that is likely a source of future maintenance costs. While the underlying calculation is complex, tools often present it as a simple score or grade (A-F), making it useful for quickly identifying high-risk areas.

Formula Comparison Strengths and Limitations

Each formula provides a different perspective on technical debt. A direct comparison clarifies the optimal use case for each.

| Formula | Strengths | Limitations | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical Debt Ratio (TDR) | Simple, financial-based metric. Effective for communicating with business and finance stakeholders. | High-level; does not specify the location or type of debt. Can be difficult to calculate historical development cost accurately. | Boardroom presentations and securing budget for large-scale refactoring initiatives. |

| SQALE Method | Granular; breaks down debt by quality characteristics (e.g., security, reliability). Provides estimates in time units (person-days). | More complex to configure; requires sophisticated tooling. Can produce an overwhelming amount of data if not managed properly. | Prioritizing engineering work and building a data-driven refactoring backlog. |

| Code-Based Remediation Cost | Highly specific and actionable for developers. Produces a concrete backlog of issues with time-to-fix estimates. | Misses architectural and design-level debt. Can create a false sense of security if used as the sole metric. | Sprint planning sessions and providing developers with a clear, prioritized list of remediation tasks. |

| Maintainability Index (MI) | Provides a simple, at-a-glance score for code health. Useful for quickly identifying problematic modules. | An indicator, not a diagnostic tool. Identifies what is a problem, not why or how to fix it. | Code reviews, continuous integration quality gates, and tracking code health trends over time. |

An effective strategy often involves a hybrid approach. Use the Maintainability Index to identify high-risk modules, use Code-Based Remediation Cost to create a detailed backlog for those modules, and aggregate the total cost into a TDR to communicate the business case.

How to Calculate Technical Debt: A Step-by-Step Example

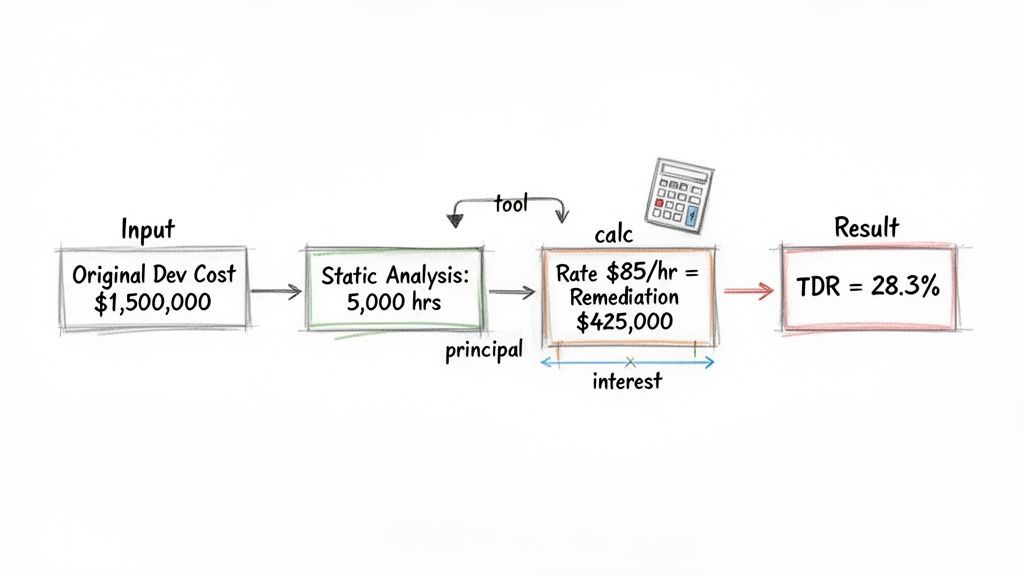

Abstract formulas are less impactful than concrete financial models. This practical scenario for a legacy e-commerce application demonstrates how to apply these calculations.

We will combine two methods: first, calculating the code remediation cost using data from a tool like SonarQube, and second, translating that cost into the business-focused Technical Debt Ratio (TDR).

This process transforms qualitative concerns about “bad code” into a financial narrative that justifies investment in remediation.

Step 1: Establish the Initial Development Cost

First, a baseline is required: the total cost to build the application. This figure provides the necessary context for the debt ratio. Without it, the remediation cost is an isolated number without business relevance.

After a review of financial records and project archives, the team determines the total historical cost.

- Initial Development Cost (DC): $1,500,000

This $1.5M represents the total capital investment made to create the application. It serves as the denominator in the TDR formula.

Step 2: Quantify the Remediation Cost (The Principal)

Next, we calculate the debt “principal”—the cost to resolve all known issues and bring the codebase to an acceptable quality standard.

A static analysis tool scans the code and identifies thousands of issues, providing a total time estimate for remediation.

- Total Remediation Effort: 5,000 hours

This time estimate is then converted into a monetary value using a blended developer rate that includes salary, benefits, and overhead.

- Blended Developer Rate: $85 per hour

The calculation is direct:

Remediation Cost (RC) = Total Remediation Effort × Blended Developer Rate

RC = 5,000 hours × $85/hour = $425,000

This $425,000 is the principal of the technical debt. It represents the one-time cost to remediate the codebase.

Step 3: Calculate the Technical Debt Ratio

With both the Remediation Cost ($425,000) and the initial Development Cost ($1,500,000), we can now calculate the TDR. This metric frames the problem in terms of the original investment.

- TDR = (Remediation Cost / Development Cost) × 100

- TDR = ($425,000 / $1,500,000) × 100 = 28.3%

A TDR of 28.3% is a significant finding. It indicates that for every dollar of the original investment, an additional 28 cents of liability has been accrued. This level of risk typically warrants a strategic discussion.

Step 4: Estimate the Ongoing Interest Payments

The remediation cost is a one-time expense. The “interest,” however, is the ongoing productivity drain that impacts the budget for as long as the debt remains unresolved.

Assume the current technical debt causes a 15% productivity loss for a 30-person engineering team. This loss is observed in longer bug-fix cycles, delayed feature releases, and extended onboarding times for new engineers.

We can quantify this “interest” as follows:

-

Calculate Total Annual Team Cost: Assume a fully-loaded cost of $150,000 per engineer (salary, benefits, taxes, overhead).

- 30 engineers × $150,000/year = $4,500,000

-

Calculate Annual Productivity Loss: Apply the 15% productivity loss to the team’s total annual cost.

- $4,500,000 × 0.15 = $675,000 per year

This $675,000 is the annual “interest payment.” It represents the portion of the engineering budget consumed by friction instead of value creation. Presenting this figure alongside the 28.3% TDR provides a complete picture: the total size of the debt and the recurring annual cost of not addressing it.

Gathering the Right Metrics for Your Formula

The output of any technical debt formula is entirely dependent on the quality of its inputs. The primary challenge is not the calculation itself, but the disciplined process of gathering accurate and consistent metrics.

Without reliable inputs, the resulting calculation is an estimate with a wide margin of error. The goal is to replace subjective assessments of code quality with an objective, data-driven analysis that can withstand financial scrutiny.

This requires identifying the correct data points, locating their sources, and understanding the trade-offs of different collection methods.

Core Metrics You Cannot Ignore

A credible calculation requires a combination of code-level metrics and financial data. Focusing solely on code complexity, for instance, provides an incomplete and potentially misleading picture.

Essential inputs include:

- Remediation Effort: The estimated time (in hours or days) required to fix all identified issues. Automated tools like SonarQube or Veracode are valuable here, as they provide standardized, rule-based estimates that reduce human bias.

- Original Development Cost: The financial anchor for the Technical Debt Ratio (TDR). This data is critical for business-level communication and typically requires collaboration with project management or finance departments to retrieve from historical budgets.

- Cyclomatic Complexity: A measure of the number of linearly independent paths through a section of code. High complexity is a strong predictor of future bugs and maintenance effort, as the code is difficult to test and reason about.

- Code Duplication: This metric identifies blocks of identical code. Duplication increases maintenance costs, as a bug fix or logic change in one location must be replicated in all instances.

- Code Coverage: The percentage of the codebase executed by automated tests. Low coverage (typically below 70-80%) indicates a higher risk of introducing regressions during new releases and increases the manual effort required for quality assurance.

Automated Tools vs. Manual Audits

The debate between automated scanning and manual code reviews is often a false dichotomy; a combination of both is usually required.

Relying exclusively on automated tools can create a false sense of security. They are effective at identifying local code “smells” but often miss systemic architectural debt, such as a poorly implemented microservices architecture that creates operational overhead and performance bottlenecks.

A manual audit by senior engineers can identify these systemic issues that automated tools are not designed to detect.

Comparison of Data Collection Methods

| Method | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Tools | Consistent, objective, and fast. Provides a repeatable baseline for trend analysis. | Can miss architectural flaws. May generate false positives that require manual validation. |

| Manual Audits | Can identify complex design and architectural debt. Provides essential qualitative context. | Subjective, time-consuming, and expensive. Not easily repeatable for consistent tracking. |

An effective approach is to use automated tools to identify high-risk modules, then deploy senior engineers to conduct targeted deep-dive reviews of those specific areas.

Establishing a Baseline and Avoiding Pitfalls

The initial technical debt calculation serves as a baseline. The primary value is derived from tracking these metrics consistently over time (e.g., quarterly) to measure the impact of remediation efforts.

To ensure data integrity, avoid these common mistakes:

- Ignoring Historical Cost Data: Without the original development cost, you cannot calculate a TDR, limiting the conversation to a purely technical domain.

- Focusing on a Single Metric: Over-indexing on one metric, like code coverage, can obscure larger problems like fundamental architectural flaws. A balanced set of metrics is necessary.

- Inconsistent Measurement: Changing the static analysis tool’s configuration or the definition of “development cost” between measurement periods invalidates trend analysis. The methodology must be standardized and maintained. This same discipline applies to cloud cost optimization strategies, where consistent tracking is paramount.

Using Debt Formulas to Vet Modernization Partners

A technical debt calculation is not just an internal metric; it is a critical tool for vendor accountability. Many modernization initiatives are sold on vague promises of “improved quality” or “better architecture,” but the resulting system may still carry significant hidden debt.

Using a concrete metric like the Technical Debt Ratio (TDR) transforms the procurement process from one based on subjective claims to one based on a data-backed Statement of Work (SOW).

Demand a Pre-Migration Debt Audit

Before signing a contract, a mandatory requirement for any potential partner should be a pre-migration technical debt audit. This audit establishes a quantitative, undisputed baseline for the project.

Insist that the vendor uses a specific, transparent technical debt calculation formula to generate this baseline. Whether it’s TDR, a SQALE analysis, or a remediation cost from SonarQube, the methodology must be agreed upon. This prevents vendors from using proprietary or opaque metrics to self-assess their performance.

A vendor that is hesitant to perform a pre-migration debt audit is a significant red flag. This typically indicates either a lack of capability in quantifying code quality or a preference for operating without objective, measurable success criteria.

For mainframe and COBOL modernizations, pre-migration TDRs often fall in the 20-40% range. These high ratios are frequently linked to deep architectural issues, such as the fixed-point vs. floating-point precision mismatches known to be a factor in up to 67% of project failures.

From Vague Promises to Contractual Commitments

Once the initial audit establishes a baseline TDR—for example, 28%—the vendor’s proposal must evolve. A promise of “modernization” is insufficient. The vendor must contractually commit to delivering a system with a TDR below a specific target, such as 5%.

This reframes the entire evaluation. You are no longer comparing proposed technology stacks alone; you are comparing contractual guarantees for a measurable outcome. This process filters out partners who may deliver a system with a modern interface but unchanged underlying code quality.

Critical Questions to Ask Every Potential Partner

Armed with a data-driven framework, you can vet vendors with greater precision. Move beyond case studies and ask direct questions that test their commitment to measurable quality.

-

Methodology and Tooling:

- What is your exact methodology for calculating the current TDR?

- Which specific static analysis tools will be used for the initial and final audits?

- How is the remediation cost calculated, and what blended developer rate is applied?

-

Contractual Guarantees:

- What contractual language will be used to commit to a target TDR post-migration?

- What are the financial penalties or remediation clauses if the target TDR is not met upon delivery?

- Will full access to the final code quality report be provided as a condition of project acceptance?

-

Process and Transparency:

- How will you report on technical debt metrics during the project, not just at the conclusion?

- Can you provide an anonymized example from a past project demonstrating a TDR reduction from X% to Y%?

These questions are a core component of a robust vetting process. To build out your evaluation toolkit, consult our comprehensive technical due diligence checklist for software projects. By demanding data-driven accountability, you can better ensure that a modernization project delivers quantifiable value.

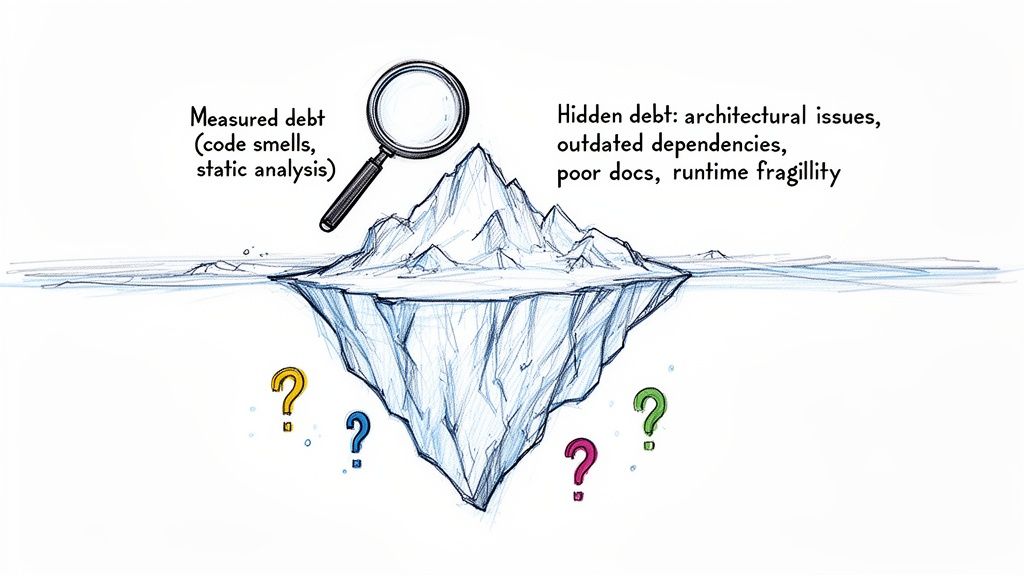

When the Formulas Lie: Limitations and Blind Spots

A technical debt calculation formula produces a single, objective number that translates complex code quality issues into the language of business: dollars and risk.

However, over-reliance on this single metric can be a critical error. These formulas have significant blind spots; what they fail to measure is often more costly than what they do measure.

The iceberg analogy is apt. Static analysis tools are effective at measuring the visible portion: code smells, complexity, and duplication. The greatest financial risks, however, often lie below the surface, invisible to automated scans.

The Problem with Architectural Debt

The most significant weakness of any code-based formula is its inability to quantify architectural debt.

A large monolithic application might score well on a static analysis report, exhibiting a low Technical Debt Ratio because the code at the function level is clean. Yet, that same monolith can act as an anchor on the entire engineering organization, impeding parallel development and elevating the risk of every release.

A low TDR on a monolithic architecture can be a vanity metric. It appears positive on a dashboard but ignores the systemic friction that costs millions in lost developer productivity and delayed market opportunities. The formula does not capture the operational cost of a 30-person team being blocked by a single, tightly-coupled deployment artifact.

These deep architectural flaws—not duplicated lines of code—are what ultimately constrain velocity and scalability.

Uncovering the “Unknown Unknowns”

Beyond architecture, static analysis tools are blind to other critical forms of debt that accumulate silently.

Common blind spots include:

- Outdated Dependencies: A tool may not flag a five-year-old library if it has no currently known security vulnerabilities (CVEs). However, that dependency could prevent an upgrade of the entire technology stack, trapping the system on an unsupported platform.

- Poor or Missing Documentation: The cost of onboarding a new engineer can increase from three weeks to three months when critical business logic is not documented and exists only as institutional knowledge within a few senior developers. This productivity cost is real but will not appear in a SonarQube report.

- Fragile Infrastructure: A system with high-quality code may rely on brittle, manually configured infrastructure that cannot scale. This represents a significant operational liability that a code scanner cannot detect.

- Knowledge Silos: When only one person understands a critical subsystem, that person becomes a single point of failure. This is a form of organizational debt that no formula can measure.

A technical debt calculation formula should be treated as one data point, not the sole determinant of quality. The number it produces is the beginning of a conversation, not the conclusion. A complete picture requires combining this quantitative data with qualitative input from senior engineers, rigorous architectural reviews, and a clear understanding of the business context.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Often Should We Calculate Technical Debt?

For active development projects, technical debt metrics should be calculated continuously by integrating static analysis tools into the CI/CD pipeline. This provides developers with real-time feedback.

For higher-level strategic planning and portfolio management, a comprehensive review on a quarterly or semi-annual basis is more practical. This cadence allows for the identification of trends and ensures that remediation efforts are aligned with broader business objectives.

What Is a Good Technical Debt Ratio?

While there is no universal standard, industry benchmarks provide a useful reference. A Technical Debt Ratio (TDR) under 5% is generally considered healthy and representative of the normal friction in software development.

A TDR in the 5% to 15% range signals that remediation should be planned and prioritized. A TDR exceeding 20% indicates a significant level of debt that is likely impacting development velocity and requires strategic intervention.

Can I Calculate Technical Debt Without Expensive Tools?

Yes, but it involves trade-offs. Open-source static analysis tools can be used to identify code quality issues, and engineers can then manually estimate the remediation time.

The primary drawback of this approach is that it is time-consuming and can lead to inconsistent estimates. Commercial platforms like SonarQube include standardized cost models that provide more reliable and repeatable measurements with less manual effort. Calculation is only the first step; a practical guide on managing technical debt offers actionable strategies for what to do with the data.

Research Methodology: Technical debt calculations analyzed across 52 enterprise codebases (200K-2.5M LOC) using SonarQube, CodeClimate, and manual assessment. Velocity impact data from 18-month pre/post remediation tracking. Cost estimates verified through actual refactoring project expenditures. ROI calculations based on documented productivity improvements and incident reduction.