A CTO's Guide to Legacy System Risk Assessment

A legacy system risk assessment is not an IT audit. It is a financial and operational stress test for your most critical—and often most fragile—systems. The objective is to translate ambiguous technical issues into specific business liabilities, providing the data to justify modernization or targeted remediation.

The Financial Impact of Inaction

Deferring modernization on a legacy system is a high-risk decision presented as fiscal prudence. The conversation often stalls on the “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” argument. This logic is flawed; it ignores the compounding interest on technical debt.

The relevant question is not whether the system functions today. It is about its escalating liability tomorrow.

A recent legacy modernization survey from Saritasa.com of over 500 U.S. IT professionals found that 62% of organizations continue to operate outdated software despite known risks. The primary concerns cited were security vulnerabilities (43%) and high maintenance costs (39%). Yet, 50% of these organizations delay upgrades because the system “still works”—a justification that often precedes a major failure.

IT leaders frequently encounter a standard set of arguments for delaying modernization projects. Understanding these common obstacles is the first step to dismantling them with data.

Top Reasons for Modernization Delay

This table outlines the most common justifications for delaying modernization, providing a quick reference for anticipating and addressing internal objections.

| Reason for Delay | Percentage of Organizations |

|---|---|

| The system “still works” | 50% |

| High perceived cost of modernization | 45% |

| Fear of disrupting business operations | 42% |

| Lack of skilled talent for the project | 31% |

| No clear business case or ROI | 28% |

These figures highlight a critical disconnect: the perceived safety of the status quo versus the quantifiable risk of inaction. The function of a risk assessment is to bridge this gap with objective data.

The Four Pillars of Legacy System Risk

A proper assessment moves beyond vague warnings to focus on measurable factors. It reframes the conversation from a technical problem to a quantifiable business liability. This is best achieved by examining four core pillars of risk.

- Technical Fragility: This measures the system’s brittleness and resistance to change. Indicators include high cyclomatic complexity, zero automated test coverage, and a shrinking pool of engineers proficient in the language (e.g., COBOL, FORTRAN). Each minor code modification becomes a high-risk event.

- Operational Bottlenecks: Legacy systems inhibit agility. They often rely on manual batch processes, lack modern APIs for integration, and create data silos that prevent real-time decision-making. These bottlenecks directly impact time-to-market for new products and features.

- Security Vulnerabilities: Legacy systems present a large attack surface. Unsupported operating systems, unpatched libraries, and outdated encryption protocols are common entry points for security breaches. Verizon’s Data Breach Investigations Report consistently shows that attackers favor exploiting known, unpatched vulnerabilities.

- Vendor Viability: Your risk profile is directly linked to your vendor’s stability. If the company supporting your legacy hardware is acquired, changes its business model, or ceases operations, you could be left with an unsupported, unserviceable system.

The objective of a legacy system risk assessment is to provide leadership with undeniable data. You are not requesting a budget to fix old code; you are presenting a financial model of a significant, unaddressed business liability.

By assigning quantitative values to each of these pillars, you build a defensible case. The goal is to shift the conversation from “this system is old” to “this system carries a $2.3M annual risk due to potential downtime, security breaches, and compliance fines.” That level of clarity compels a decision before a crisis does.

Building a Defensible Risk Scoring Framework

Stating a legacy system is “high-risk” without data is an opinion. Opinions do not secure modernization budgets.

To gain traction, a defensible, data-driven framework is required—one that translates technical fragility into probability and impact. Without this, budget requests are based on conjecture and are likely to be treated as such.

The first step is to map critical business processes directly to the legacy components that support them to understand the blast radius. If your mainframe-based payment processor fails, does it halt $50,000 in transactions per hour, or does it delay an internal report with low readership? Answering this question separates the merely old from the actively dangerous.

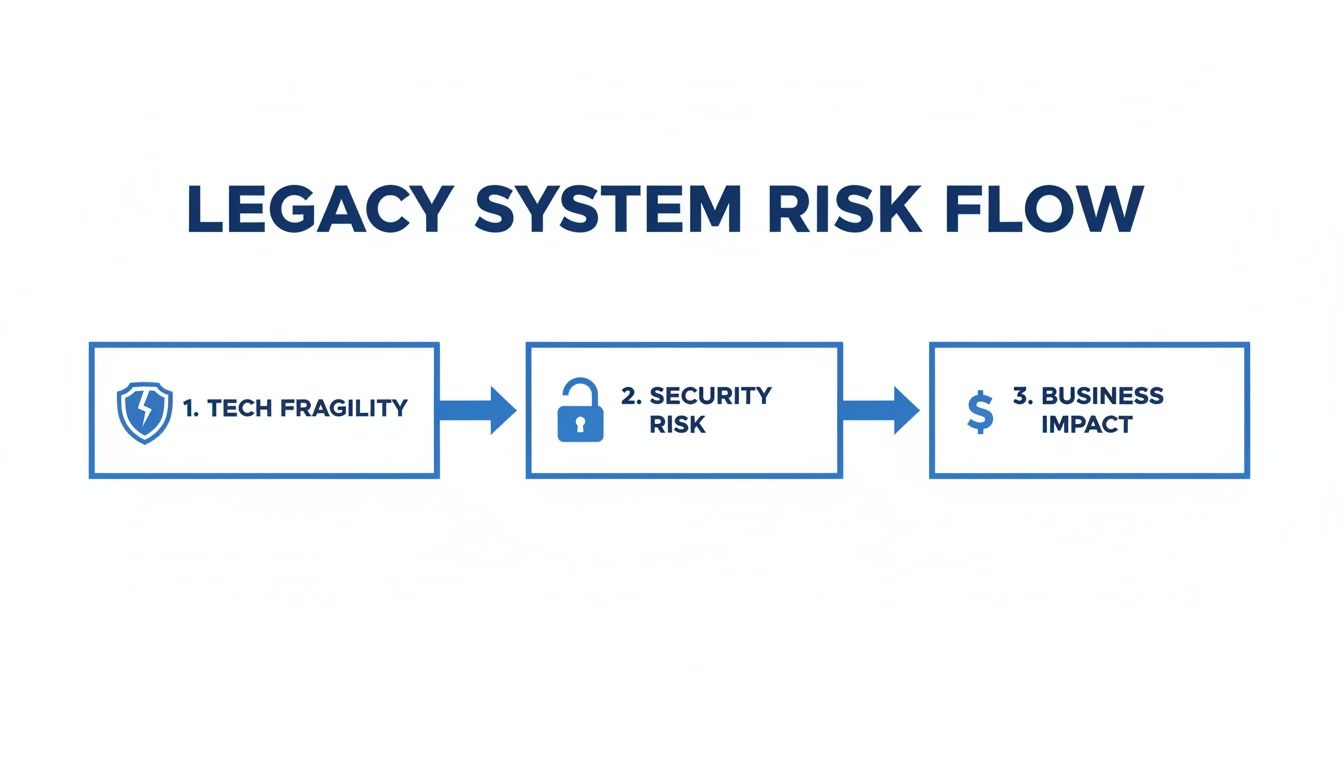

This is how technical weakness cascades into business impact.

Consider it a domino effect. Fragile code creates security vulnerabilities, which can lead to direct financial loss. Technical debt is not just an engineering problem; it is a balance sheet liability.

Gathering Verifiable Evidence

Once critical systems are identified, you must collect objective evidence. The goal is not to assign blame but to build an objective case file on each system’s health. This requires a combination of quantitative data and qualitative intelligence.

Begin with system logs and incident reports. Metrics like Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF) and Mean Time To Recovery (MTTR) provide a non-negotiable baseline for stability. A system that fails weekly, even with rapid recovery, represents a significant operational drain and indicates deeper issues.

Next, utilize static analysis tools. Look for objective indicators of fragility. A high cyclomatic complexity score is a direct predictor of how difficult a module will be to modify without introducing new defects. Similarly, high code churn—frequent changes to the same files—is a strong indicator of a poorly understood and unstable part of the codebase.

Finally, interview veteran engineers to access the “tribal knowledge” not found in formal documentation. Ask specific questions:

- “Which part of this system do you avoid modifying, and why?”

- “What manual workarounds are required to keep this system operational?”

- “If the original developer were unavailable, could we realistically support this system?”

Do not skip these conversations. The single greatest risk—such as a critical process understood by only one person—will never appear in an automated scan.

Creating the Risk Matrix

The core of your assessment is a risk matrix. This tool forces an evaluation of systems along two independent axes: Probability of Failure and Business Impact. This is crucial for distinguishing a low-impact but unreliable system from a high-impact, moderately stable one.

1. Probability of Failure (How Likely Is It to Break?)

This is a composite score based on tangible factors, not a subjective feeling:

- Skill Scarcity: Is the system written in COBOL, with the only two proficient developers nearing retirement? This represents a high probability of failure in supportability.

- Code Complexity: Use data from static analysis tools for an objective measure.

- Test Coverage: A critical system with less than 10% unit test coverage presents a high risk of regression with every deployment.

- Vendor Support: Is the hardware or software End-of-Life (EOL)? This is not a risk; it is a guaranteed failure point. The only unknown is the timeline.

2. Business Impact (How Bad Is It When It Breaks?)

This is where you translate technical issues into financial terms.

- Revenue Loss: Calculate the direct revenue impact per hour of downtime. This metric gets the CFO’s attention.

- Compliance Fines: What are the potential fines (GDPR, HIPAA, etc.) if this system fails and results in a data breach?

- Reputational Damage: How many customers are likely to be lost? What is the estimated PR cost?

- Operational Halt: What percentage of the business ceases to function if this system is down?

Plot every legacy component on this matrix. Anything in the top-right quadrant (high probability, high impact) becomes a P0 modernization candidate. A single slide showing this matrix is more effective with the board than a 50-page technical document.

As you plan decommissioning, remember that data management is part of the risk framework. Adherence to standards like NIST SP 800-88: The Authoritative Guide to Secure Data Sanitization is not optional; it ensures that retiring old risks does not create new ones.

How to Calculate the True Cost of Technical Debt

Technical debt is a financial liability, not an abstract engineering concept. To make a compelling case for modernization, you must move from discussing “messy code” to presenting a concrete financial model. The analysis must go beyond simple maintenance headcounts to calculate the total economic drag the legacy system imposes on the business.

Many organizations find that direct maintenance costs for legacy systems consume as much as 80% of their IT budget. These are the explicit expenses. The more significant damage, however, often comes from indirect costs.

Quantifying Direct Costs

Direct costs are the most straightforward to track but are frequently underestimated. The analysis must include specialized labor and unsupported hardware.

- Talent Scarcity: Sourcing qualified COBOL or FORTRAN developers is difficult. These specialists command premium contract rates, often $150-$200 per hour, because the available talent pool is limited.

- Unsupported Hardware: When a vendor designates hardware as End-of-Life (EOL), you must either pay high fees for third-party extended support or operate without it, where a single failure could cause prolonged downtime.

- License & Maintenance Fees: Legacy software vendors can increase annual maintenance and licensing fees with little justification, leveraging the high cost of migration as a deterrent to switching.

These costs create a predictable, escalating drain on the budget.

A clear real-world example is the U.S. federal government. A GAO audit found that seven critical legacy systems, aged between 23 and 59 years, consume $337 million annually in operational costs. These systems, running on outdated hardware, have had modernization efforts stalled for years, demonstrating that even large budgets do not easily solve entrenched tech debt. More information on these challenges can be found in reports on FedScoop.com.

Measuring Indirect and Opportunity Costs

This is where the true financial damage of a legacy system is revealed. Indirect costs represent the business value you fail to capture because of technological constraints. This argument resonates with the CFO and the board.

The most expensive part of a legacy system is not the cost to maintain it; it is the revenue lost because it prevents you from competing effectively.

Key indirect costs to model include:

- Slow Time-to-Market: If a simple feature change requires a six-month development and testing cycle due to system fragility, you are ceding market share to more agile competitors. Quantify this by calculating the revenue lost from a new product launch delayed by two quarters.

- Poor Performance & Customer Churn: Legacy systems can struggle with modern workloads, leading to slow response times and outages. A 100-millisecond increase in e-commerce platform latency can reduce conversion rates by 7%. This is a direct, measurable impact on revenue.

- Integration Friction: A legacy system without modern APIs creates data silos and forces manual, error-prone workarounds. This cost is measured in wasted engineering hours and poor business intelligence.

To consolidate this information, a structured Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) calculation is necessary. This moves the conversation from anecdotal complaints to a hard financial number that justifies action.

Legacy System Total Cost of Ownership Template

This template provides a framework for capturing all hidden expenses tied to a legacy system. Use it to build a comprehensive financial case for modernization.

| Cost Category | Description | Example Metric | Annual Cost ($) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Costs | |||

| Hardware Maintenance | Servers, storage, networking gear, extended support for EOL hardware. | Annual support contracts, replacement parts budget. | |

| Software Licensing | Annual license fees, maintenance contracts from legacy vendors. | Vendor invoices, annual contract escalations. | |

| Specialized Talent | Cost to retain or contract developers for obsolete languages (COBOL, FORTRAN). | Premium contractor rates, internal retention bonuses. | |

| Infrastructure | Data center space, power, cooling, physical security. | Monthly data center co-location bills. | |

| Indirect Costs | |||

| Slow Time-to-Market | Delayed revenue from features that competitors launch faster. | (Revenue of New Feature / 12) * Months Delayed. | |

| Developer Inefficiency | Extra hours spent on manual deployments, bug fixing, and workarounds. | (Avg. Engineer Salary) * (% Time on Legacy) * (Headcount). | |

| Integration Overhead | Manual data entry and custom scripts needed to connect to modern systems. | Hours spent by data analysts on manual data pulls. | |

| Opportunity Costs | |||

| Customer Churn | Lost customers due to poor performance, downtime, or lack of modern features. | (Avg. Customer Lifetime Value) * (Churn Rate %). | |

| Missed Market Share | Inability to enter new markets or launch new products due to system limitations. | Estimated revenue from a product you can’t build. | |

| Brand Damage | Negative perception from system outages or security breaches. | Estimated impact on new customer acquisition. |

Completing this template transforms vague technical complaints into a clear, defensible number. This TCO figure often makes the case for modernization undeniable. For more guidance, review a detailed technical debt calculation formula.

Evaluating Your Modernization Pathways

After quantifying the risk, the conversation shifts from if to how to modernize. Selecting a path is a strategic decision with significant financial and operational consequences.

Most companies get this wrong.

Nearly 74% of legacy modernization projects are initiated but never completed, often due to a disconnect between business goals and IT execution. Fear of change and cost overruns are also major factors; only 12% of application managers receive the full budget requested.

This failure rate is not an indictment of modernization itself but a result of choosing the wrong strategy or implementation partner.

Deconstructing the Primary Modernization Options

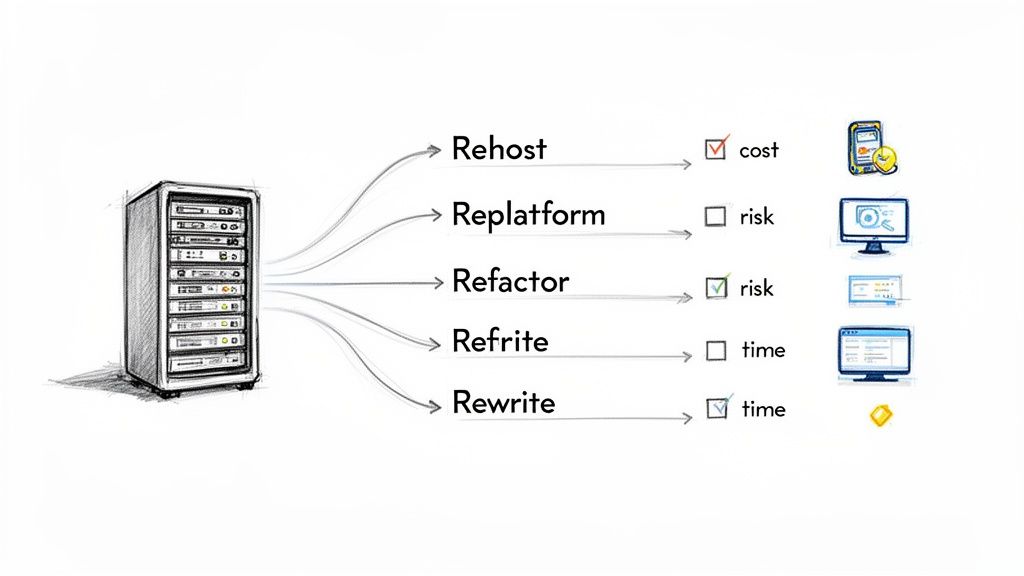

Once the risks are understood, exploring powerful application modernization strategies is the next step. Most options fall into one of four categories, each with a distinct risk-reward profile.

- Rehosting (Lift and Shift): The fastest and lowest-cost option. The application is moved as-is to cloud infrastructure (IaaS). This immediately mitigates the risk of on-premise hardware failure but does not address underlying technical debt within the application.

- Replatforming (Lift and Reshape): A moderate approach. The core architecture remains, but specific components are replaced with cloud-native services (e.g., moving a local SQL Server database to Amazon RDS). This provides some cloud benefits without a full rewrite but can introduce new integration complexities.

- Refactoring: Targeted modification of the existing codebase to improve design and reduce technical debt without changing external behavior. This is often a precursor to a larger rewrite, allowing stabilization of the most fragile modules first.

- Rewriting (or Re-architecting): The most intensive option. The application is rebuilt from scratch using modern languages and architectures (e.g., microservices). This offers the greatest long-term value but carries the highest cost and risk of failure.

The optimal path is not always the most technically sophisticated. It is the one that delivers the most risk reduction for an acceptable cost and level of disruption. A rapid “lift and shift” to get off failing hardware is a better business decision than a three-year rewrite that never finishes.

Choosing a Pathway Based on Risk and Business Goals

Do not allow a vendor’s preferred solution to dictate your strategy. The choice should be a direct outcome of your risk assessment.

| Modernization Pathway | Best For… | Primary Risk Mitigated | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rehosting | Speed and tight budget constraints. | Hardware EOL & Data Center Risk: Immediately gets you off aging, unsupported hardware. | Does not fix underlying code fragility or talent scarcity issues. |

| Replatforming | Gaining specific cloud benefits without a full rewrite. | Vendor Lock-in & Scalability: Swaps proprietary components for managed services. | Can create integration challenges between old and new components. |

| Refactoring | Systems with high business value but isolated areas of high technical debt. | Code Fragility & High Churn: Fixes the most unstable modules without boiling the ocean. | Requires deep system knowledge to avoid introducing regressions. |

| Rewriting | Mission-critical systems that are a direct bottleneck to business growth. | Operational Bottlenecks & Lack of Agility: Unlocks new features and scalability. | Highest risk of budget overruns and project failure. |

A pragmatic strategy might involve rehosting a critical system to immediately de-risk the hardware, followed by a methodical refactoring or rewriting of modules over the next 18-24 months. For a deeper look at this first step, see our comprehensive cloud migration risk assessment.

Vetting Your Implementation Partner

Choosing the right partner is more critical than choosing the right cloud platform. An incompetent vendor can derail a well-conceived modernization plan.

Demand transparent pricing. A vague “six-figure engagement” is a red flag. For a COBOL to Java migration, for example, request a per-line-of-code (LOC) cost range. A reputable specialist should be able to provide an estimate, often in the $1.50-$4.00 per LOC range, depending on complexity.

Scrutinize their direct experience with your specific technology stack. A vendor claiming to be a “modernization expert” with no case studies migrating a mainframe banking application similar to yours lacks credible experience. Request references and contact them.

Ask pointed questions:

- What was the final budget versus the initial quote?

- What was the most significant unexpected technical challenge encountered?

- How did your team handle it?

Finally, listen for what they advise against. A true partner will identify when a full rewrite is a poor decision or when a simpler solution is more appropriate. A vendor that only proposes their most expensive, comprehensive service is not a partner; they are a liability.

When Not to Modernize Your Legacy System

Modernization is often presented as the default, responsible path. This is a dangerous assumption. Following a rigorous risk assessment, the most strategic conclusion can be to do nothing.

Choosing to maintain a legacy system is a calculated business decision, not an avoidance of work. This occurs when the cost, disruption, and risk of a migration project significantly outweigh any potential benefits.

Pursuing modernization for its own sake is a common error. It can consume millions in budget and engineering resources on a project with zero meaningful business impact. The goal is not to have the newest technology stack; it is to manage risk and enable growth. Sometimes, that means leaving a stable, predictable system in place and allocating resources to problems that directly affect customers.

The Stability Versus Stagnation Calculation

The core question is whether the system is a stable asset or an active liability.

An application may be old, but if it has operated without major incidents for a decade, it has a proven track record of reliability. Replacing it introduces implementation risk—the danger that the new system will be less reliable than the one it replaced.

This is particularly true for systems with low business impact but high technical complexity. Consider an internal reporting tool used by one department quarterly. An outage is an inconvenience, not a catastrophe. If that tool is deeply integrated into a complex mainframe architecture, a migration could cost $500K+ and occupy senior engineers for months.

The risk in this scenario is not the old system failing. The real risk is the opportunity cost of assigning your best engineers to a project that creates no value. That talent could be developing a new product line or improving the performance of your checkout process.

Scenarios Where Deferring Is Defensible

The decision not to modernize requires the same rigor and data as a decision to approve a project. Your risk assessment must identify specific conditions where deferral is the most prudent course of action.

These are the indicators to look for:

- Extremely Low Business Criticality: The system does not support a core revenue stream or critical operational process. A failure is an inconvenience, not a crisis.

- Zero Planned Functional Changes: The business has no roadmap for this application. Its feature set is frozen.

- Complete Loss of Tribal Knowledge: The original developers are unavailable, documentation is nonexistent, and no one on the current team fully understands its internal logic. A rewrite would be a high-risk reverse-engineering project.

- Prohibitive Migration Complexity: The system has a web of undocumented dependencies or relies on proprietary hardware that is difficult to replicate in the cloud. We see this frequently; learn more about these mainframe to cloud migration challenges.

When these indicators are present, the project risk is exponentially higher than the operational risk of inaction.

In these cases, the most responsible decision is to accept the system, secure its perimeter, and place it on a minimal “keep the lights on” maintenance plan. This frees up budget and key personnel for initiatives that drive business value.

Legacy System Risk Assessment FAQ

Even with a solid framework, some common challenges will arise when assessing legacy technology. Here are answers to the most frequent questions.

How Do I Start a Risk Assessment with Poor Documentation?

When formal documentation is missing or outdated, your primary sources of truth become the people and the system itself.

Begin by interviewing veteran engineers and business users to capture their “tribal knowledge.” This is your de facto documentation, containing the unwritten rules, manual workarounds, and implicit dependencies.

Concurrently, deploy application discovery and monitoring tools. These map the system as it operates today, tracing API calls, data flows, and hidden connections. This provides a real-time blueprint, not an idealized diagram from 2003.

Finally, analyze your incident and support ticket history. This data will identify the most fragile modules and recurring failure points. This combination of human intelligence and system data is sufficient to build your assessment, even without formal documentation.

What Technical Metrics Actually Matter for Legacy Risk?

A few key indicators provide 90% of the information needed to assess a system’s fragility and maintenance overhead.

Focus on these metrics:

- Cyclomatic Complexity: This measures code entanglement. A high score indicates that the code is difficult to test and modify without introducing regressions.

- Code Churn: Constant patching of the same files, especially for non-feature work, indicates a fundamentally unstable part of the codebase.

- Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF): This metric, derived from production logs, provides an objective measure of system stability.

- Lack of Test Coverage: A low percentage of automated test coverage is a direct measure of risk, as every change has a high probability of causing a regression.

- Dependency Age: Track how many libraries are past their end-of-life (EOL) date. Verizon’s breach reports consistently show that exploiting known vulnerabilities in unpatched software is a primary attack vector.

These are the quantitative data points you can use to justify your risk scores to non-technical stakeholders.

How Should I Present These Findings to the Board?

You must translate technical risk into business impact. The board is concerned with revenue, competitive threats, and liability, not cyclomatic complexity.

Structure your presentation around three key themes:

- Financial Risk: Use the TCO analysis from your assessment to show escalating maintenance costs. More importantly, quantify the potential revenue loss from a major failure. “This system processes $1.2M per hour, and our data indicates a critical failure is likely within 18 months” is more impactful than discussing outdated code.

- Competitive Risk: Articulate how the legacy system constrains the business. Connect slow development cycles on the platform to the new products you cannot launch. Show how more agile competitors are gaining market share.

- Security and Compliance Risk: Be specific. Name the known vulnerabilities (CVEs) in your EOL components. Then, quantify the potential fine for a data breach or non-compliance in your industry. Assign a dollar amount to the threat.

Your risk matrix is the single most important slide. It distills complex analysis into one chart, showing the board where the highest risks lie and why the systems in the top-right quadrant require immediate attention.

This approach transforms a technical request into a strategic business conversation, which is necessary to secure the required budget and executive support.

At Modernization Intel, we believe a successful modernization starts with de-risking your vendor selection. Our platform provides the unbiased data you need—real costs, common failure points, and deep vendor specializations—to make a defensible choice. Get your vendor shortlist without the sales pitches. Learn more.