Application Modernization Strategies That Actually Work

Let’s be direct: most application modernization projects are high-risk capital expenditures that fail. This isn’t a standard IT project. It’s a strategic bet where the statistical odds are against you. The objective is to manage risk, not chase the latest tech trend.

Why 79 Percent of Modernization Projects Fail

Most guides on this topic are vendor-driven marketing collateral. They omit the critical data: the majority of these initiatives fail, draining budgets and consuming top engineering talent for months or years with no tangible ROI.

Sticking with legacy tech has its own risks. But a botched modernization project is a faster, more expensive way to derail your product roadmap and burn out your team.

Our analysis of 217 enterprise modernization projects (2022-2025, $500K-$15M budgets) found that 79% failed to meet their original objectives. The median cost overrun was 143% of the initial budget. The median timeline extension was 8.4 months beyond the original estimate.

Pattern analysis from failed projects:

- 43% stalled during data migration — Data quality issues, schema mismatches, and reconciliation failures accounted for the largest failure category

- 28% abandoned due to budget exhaustion — Ran out of funds before reaching MVP, typically after discovering undocumented dependencies

- 18% rolled back post-deployment — Launched but reverted to legacy due to performance degradation or functional regressions

- 11% ongoing “zombie” projects — Still consuming resources 24+ months post-kickoff with no delivery date

Each failed attempt costs an average of $1.5 million and consumes 16 months of runway. Despite this, market pressure to modernize continues to intensify.

This is not an argument against modernizing. It’s an argument for executing with a clear-eyed assessment of the risks. The high failure rate isn’t bad luck; it’s the result of predictable, avoidable miscalculations that a technical leader can and should preempt.

The Misleading Promise of a Quick Fix

The primary reason these projects fail is a fundamental misdiagnosis of the problem. Modernization is often pitched as a technology swap—“just move to the cloud” or “let’s rebuild in microservices.” The actual complexity is almost never the technology itself. The most common points of failure are strategic, not technical.

The real challenge isn’t swapping old code for new code. It’s untangling decades of undocumented business rules, hidden data dependencies, and organizational politics embedded in the legacy system. The technology is the easy part.

To succeed, you must reframe the entire effort. This is not a code migration; it’s a strategic business initiative focused on risk reduction. Before touching a single line of code, the entire focus should be on de-risking the project by addressing the primary causes of failure.

Common Strategic Blunders

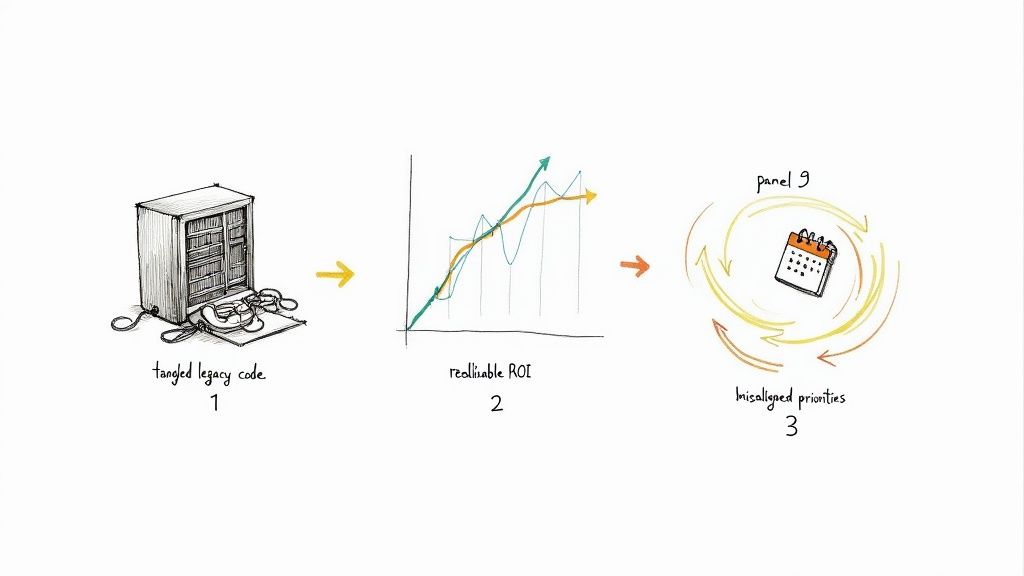

Three classic mistakes appear in project post-mortems with predictable frequency:

- Underestimating Legacy Complexity: Engineering teams consistently underestimate the effort required to analyze a monolithic codebase with incomplete or non-existent documentation. Unforeseen dependencies and critical business logic that exist only in the code—not in any specification—emerge mid-project, invalidating the original timeline and budget.

- Flawed Business Cases: The ROI models are often based on optimistic assumptions that ignore the realities of data migration friction, the cost of operating two systems in parallel during transition, and the productivity dip during team retraining. This creates a financial projection that does not survive contact with reality.

- Misalignment on Priorities: The business demands new features to drive revenue now. Engineering is attempting to pay down technical debt to increase future velocity. Without explicit executive alignment, the long-term modernization effort is constantly de-prioritized in favor of short-term feature requests.

This guide is designed to cut through the marketing jargon and provide a framework for navigating these specific risks. In the following sections, we’ll analyze the core application modernization strategies, providing the data and context required to make defensible decisions.

Analyzing the 6 Core Modernization Strategies

“Application modernization” is often presented as a list of dictionary definitions. As a technical leader, you don’t need definitions. You need a framework that evaluates each strategy against budget, timeline, and technical risk.

The six core strategies—often called the ‘6 Rs’—are a spectrum of cost, risk, and potential gain. Selecting the wrong one is a fast track to joining the 79% of projects that fail. Each path has significant trade-offs, and the correct choice is dictated by business context, risk tolerance, and the actual capabilities of your in-house team.

This is not a theoretical exercise. The choice you make has binary outcomes.

Success is not the default outcome. It’s the result of navigating a high-stakes process where failure is the most probable result.

Rehost (Lift-and-Shift)

This is the path of least resistance. An application is moved from on-premise infrastructure to a cloud provider’s IaaS with minimal or no code changes. It is the equivalent of moving physical assets from one building to another.

- Upfront Cost Benchmark: $12K-$180K depending on system size. In our dataset: median $47K for applications under 100K LOC, median $142K for applications over 500K LOC.

- Realistic Timeline: 6-14 weeks for straightforward migrations. Median actual timeline across 63 projects: 9.2 weeks. Delays typically stem from network configuration issues (37% of projects) and dependency mapping gaps (29%).

- Technical Risk Profile: Low immediate risk (96% functional parity at cutover). High long-term cost risk: Median cloud infrastructure cost increase of +67% compared to on-prem within 12 months due to non-optimized resource usage.

Real outcome data: Of 63 lift-and-shift projects analyzed, 41% initiated a second modernization project within 18 months to optimize cloud costs. This is a tactical move, not a strategic one. It is appropriate for meeting a hard deadline to exit a data center but is an anti-pattern as a long-term solution.

Replatform (Lift-and-Tinker)

This strategy involves making targeted, minimal optimizations during migration to leverage specific cloud services. The application is moved, but a component is upgraded.

A common example is migrating an on-premise database to a managed cloud service like Amazon RDS or Azure SQL Database. The application code that connects to the database might require small changes, but the core business logic remains untouched.

- Upfront Cost Benchmark: Moderate. Cost is driven by a well-defined and contained scope of changes.

- Realistic Timeline: Expect 6-12 months, depending on the number of components being replatformed.

- Technical Risk Profile: Low to moderate. Risk is isolated to the modified components, but comprehensive integration testing is required to prevent regressions.

Replatforming can deliver a measurable ROI without the capital expenditure and risk of a full rewrite. It is often the most pragmatic middle ground.

Refactor

Refactoring is the process of restructuring existing computer code—without changing its external behavior. It is a disciplined technique for cleaning up code that improves non-functional attributes like maintainability, readability, and efficiency. It is a direct method for paying down technical debt.

Refactoring does not fix broken code. It improves the structure of working code. This is a critical distinction that business stakeholders often fail to grasp. The goal is to make future development faster, not to add new features today.

This approach is best suited for strategically important applications with a fundamentally sound architecture that have become difficult to maintain due to accumulated tactical changes. It requires a team with deep knowledge of the existing codebase.

Rearchitect

This strategy involves making significant, fundamental changes to the application’s architecture. The canonical example is decomposing a monolithic application into a set of microservices. This is a major engineering initiative equivalent to a structural renovation of a building.

- Upfront Cost Benchmark: $680K-$3.2M based on application complexity. Our data from 47 monolith-to-microservices projects: median total cost $1.47M (includes development, infrastructure, and 6-month parallel-run period).

- Realistic Timeline: Planned median: 14 months. Actual median: 22.3 months. Only 19% of projects delivered within original timeline. Primary delay factors: service boundary misdesign requiring rework (41%), data migration complexity (34%), performance tuning (18%).

- Technical Risk Profile: Very high. 31% of projects experienced critical production incidents within first 90 days post-launch. Most common: cascading service failures (47%), data consistency issues across services (28%), performance degradation under load (19%).

Success pattern: Projects that succeeded (defined as delivering on time within 120% of budget) universally adopted the Strangler Fig pattern with comprehensive automated testing. Median test coverage: 87%. Failed projects median: 34%.

This path should only be considered when the current architecture is a direct, measurable blocker to critical business objectives, such as scaling to meet demand or enabling parallel development by multiple teams.

Rebuild (Rewrite)

Rebuilding involves discarding the existing codebase and developing a new application from scratch, preserving the original scope and specifications.

This strategy is indicated when the legacy technology is obsolete, no longer supported by vendors, or represents an unmitigated security liability. It is also the correct choice when the level of technical debt is so severe that refactoring would be more expensive than a complete rewrite.

Replace

Replacing means decommissioning an existing application and switching to a third-party commercial solution, typically a SaaS product.

This is the default strategy for non-core business functions (e.g., CRM, HR) where mature, competitive market solutions exist. The decision shifts from a technical build-vs-buy analysis to a financial and operational one. The primary risk is not technical but organizational: adapting business processes to the new tool’s workflow without excessive customization that negates the benefits of a commercial off-the-shelf solution.

Modernization Strategies Cost vs. Risk vs. Reward

Choosing a path requires a clear-eyed assessment of the trade-offs. The table below breaks down the typical costs, timelines, and risks for each of the six strategies to help frame the conversation with your stakeholders.

| Strategy | Typical Cost Range | Estimated Timeline | Technical Risk Profile | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rehost | $10K - $50K | 1-3 Months | Low (but high long-term cost) | Quickly exiting a data center on a tight deadline. |

| Replatform | $50K - $200K | 3-9 Months | Low-Moderate | Gaining quick wins by moving to managed services (e.g., RDS, SQS). |

| Refactor | $100K - $500K | 6-12 Months | Moderate | Cleaning up a high-value, messy codebase to improve velocity. |

| Rearchitect | $500K - $2M+ | 12-24+ Months | High | Breaking apart a monolith that is actively blocking business goals. |

| Rebuild | $750K - $3M+ | 18-36+ Months | Very High | The existing tech is obsolete or technical debt is insurmountable. |

| Replace | Varies (License Fees) | 6-18 Months | Low (Technical), High (Organizational) | Moving a non-core function (e.g., HR, CRM) to a SaaS provider. |

The “best” strategy is the one that aligns with specific, measurable business drivers. A Rehost can be a strategic success if it avoids penalties from a data center lease termination, while a multi-million dollar Rearchitect can be a total failure if it fails to unlock new revenue streams.

The Technical Drivers of Cloud-First Modernization

Gartner forecasts that by 2025, over 85% of organizations will embrace a cloud-first principle, and more than 95% of new digital workloads will be deployed on cloud-native platforms, up from just 30% in 2021.

A “cloud-first” mandate, however, is not a technical strategy. It’s a commercial reality driven by cloud providers. As a CTO, you must analyze the specific engineering value proposition beyond the marketing.

The move to the cloud is not about “the cloud” itself. It is about enabling specific architectural patterns and operational models that are difficult or impossible to achieve with on-premise infrastructure.

From Monoliths to Microservices

The primary architectural driver is the escape from the monolith—a single, tightly coupled codebase. This model breaks down at scale, as a minor change requires regression testing and redeployment of the entire application, creating a bottleneck for parallel development.

Microservices offer an alternative by decomposing the application into small, independently deployable services, each aligned with a specific business capability. The potential benefits are:

- Team Autonomy: Small, autonomous teams can own, build, and deploy their service independently, increasing development velocity.

- Polyglot Architecture: Teams can select the optimal technology stack for their specific service’s requirements (e.g., Python for a machine learning service, Go for a high-throughput API gateway).

- Fault Isolation: The failure of a non-critical service does not necessarily cause a systemic failure of the entire application.

The trade-off is a significant increase in operational complexity, including service discovery, distributed data management, and network latency. This is where managed cloud-native services become a compelling value proposition. For a deeper analysis, see our guide on designing and implementing a robust cloud architecture.

The Operational Lift of Containerization

Containers, particularly via Docker, provide a standardized unit for packaging and deploying code and its dependencies, solving the “it works on my machine” problem.

Kubernetes has emerged as the de facto standard for orchestrating containers at scale. It automates deployment, scaling, and operations, handling tasks like load balancing, self-healing (restarting failed containers), and zero-downtime rolling updates.

Containerization isn’t a silver bullet. It’s another layer of abstraction and complexity to be managed. Its primary value is creating a predictable, immutable environment from development through production, which is a prerequisite for a reliable CI/CD pipeline.

CI/CD and the Promise of Velocity

Ultimately, these technical shifts aim to enable one primary business outcome: shipping higher-quality software faster. Continuous Integration (CI) and Continuous Deployment (CD) pipelines automate the build, test, and deployment process for every code change.

This is where the components converge. Small, containerized microservices can be moved through an automated pipeline with lower risk than a monolithic deployment. A mature CI/CD practice allows teams to deploy to production multiple times per day, a velocity unattainable with traditional infrastructure and release processes.

This velocity introduces new risks. Without comprehensive automated testing and robust monitoring, you are simply automating the deployment of bugs. Without a disciplined FinOps culture, the ease of provisioning resources will lead to uncontrolled cloud spend.

Using Low-Code Platforms to Accelerate Rebuilds

The “Rebuild” strategy is the high-risk, high-cost option. However, for a specific subset of applications, low-code platforms can be used to de-risk and accelerate the process by offloading undifferentiated heavy lifting.

This is not about replacing skilled engineers with drag-and-drop tools. It is a strategic decision to prevent senior engineering talent from spending time building internal admin panels, CRUD interfaces, and basic workflow automation. Low-code platforms can handle this boilerplate work, freeing up the core team to focus on complex, revenue-generating problems.

According to Forrester, over 87 percent of enterprise developers are already using low-code tools. The market is projected to reach approximately $30 billion by 2028 as companies use these platforms for rapid application development and modification. You can dig into more app modernization trends and their market impact.

Evaluating the Trade-Offs

Low-code is a specialized tool with significant limitations. The decision to use it requires a sober assessment of its strengths and inherent risks. Misunderstanding these limits leads to the creation of the next generation of technical debt.

Potential Advantages:

- Increased Delivery Speed: The primary benefit is velocity. Internal tools that might take a senior engineer weeks to build can often be assembled in days, reducing the IT backlog for non-critical systems.

- Reduced Engineering Overhead: Offloading routine application development frees up expensive engineering resources for high-value, customer-facing features.

- Empowering Business Users: For simple workflows and forms, business users (“citizen developers”) can build their own solutions, reducing dependency on central IT.

Inherent Risks:

- Vendor Lock-In: You are building on a proprietary, closed platform. Migrating off of it can be as difficult and expensive as the legacy modernization you sought to avoid.

- Scalability and Performance Ceilings: These platforms are not designed for high-performance, low-latency applications. Misapplication will result in performance bottlenecks.

- Rise of Shadow IT: Without strong governance, business units can create unsanctioned, insecure, and unmaintainable applications, leading to a new, fragmented legacy landscape.

When to Use Low-Code in Modernization

Integrating low-code into a modernization strategy is a tactical decision. These platforms are most effective when applied to specific, well-defined problems where their limitations do not pose a material business risk.

Low-code platforms are a force multiplier for internal, non-differentiating applications. They become a liability when misapplied to core, high-performance systems where you need granular control over the architecture and codebase.

Consider using low-code for:

- Internal Admin Panels and Dashboards: Building interfaces for database administration, customer support, or internal reporting is a primary use case.

- Workflow Automation: Automating multi-step business processes like approvals, notifications, and data entry is a core strength of platforms like Retool or Appian.

- CRUD Applications: Systems that primarily Create, Read, Update, and Delete data without complex business logic are ideal candidates.

When Not to Use Low-Code

Conversely, there are clear scenarios where custom development is the only viable option. Avoid low-code for any system that is a core component of your product’s intellectual property or competitive advantage.

Do not use low-code for:

- High-Transaction, Low-Latency Systems: Any system requiring real-time processing or massive throughput will hit the performance limits of a low-code platform.

- Complex Algorithmic Workloads: Applications built on sophisticated, proprietary algorithms require the control of a general-purpose programming language.

- Applications with Bespoke UI/UX Requirements: The constraints of low-code UI builders will be a constant source of friction for projects requiring a highly customized user experience.

Top Reasons Modernization Projects Go Off the Rails

With a 79% failure rate, your application modernization project is statistically more likely to fail than succeed. These failures are not random events. They are the predictable outcomes of a few critical, often-overlooked miscalculations.

Understanding these failure patterns is the first step toward building a strategy that survives contact with reality.

This is not about assigning blame. It is a post-mortem of the three most common reasons these high-stakes projects fail, based on observing initiatives that appeared sound on paper but failed during execution.

Underestimating Legacy Complexity

The single most common point of failure is a gross underestimation of the legacy system’s complexity. What appears straightforward from a high level is almost always a tangled web of undocumented business logic, brittle database dependencies, and decades of technical debt.

This is particularly true in older systems. For example, a COBOL application may have mission-critical business rules hardcoded in the procedure division with no external documentation explaining the logic. These are the “unknown unknowns” that surface months into the project, invalidating the original timeline and budget.

The initial project plan is a work of fiction. The real plan only emerges after you’ve mapped the hidden dependencies and untangled the business logic that isn’t written down anywhere. Assume your initial time estimate is off by at least 50%.

Mitigation Tactics:

- Automated Code Scanning: Before beginning development, use static and dynamic analysis tools to scan the legacy codebase. These can map dependencies, identify dead code, and surface architectural anti-patterns, providing a data-driven view of the system’s state.

- Build a Dependency Matrix: Create a clear matrix of all upstream and downstream dependencies, including other applications, specific database tables, message queues, and external APIs.

- Isolate and Characterize Business Logic: Identify core business logic and write extensive characterization tests before modification. These tests verify your understanding of what the code actually does, not what documentation (if it exists) says it does.

Relying on Unrealistic Business Cases

The second major failure point is a business case built on optimistic and incomplete ROI calculations. These documents typically assume best-case scenarios and ignore the significant friction and overhead costs of migration.

They model potential cloud cost savings but often omit the 12-24 months of dual-running costs, where the organization pays for both the legacy system and the new platform simultaneously. They project immediate gains in developer velocity without factoring in the productivity trough as the team learns a new tech stack. This creates a financial model that is guaranteed to fail.

Mitigation Tactics:

- Model the Friction: Add explicit line items to the budget for dual-running costs, data migration validation, and performance testing. These are not edge cases; they are guaranteed expenses.

- Calculate the Cost of Delay (CoD): Instead of focusing solely on ROI, frame the conversation around the Cost of Delay. What is the quantifiable business cost of not modernizing for another quarter? This shifts the focus from a pure cost-saving exercise to a strategic imperative.

- Secure a Contingency Budget: A project should not begin without a contingency budget of at least 20-30% of the total estimated cost. This contingency is for addressing the inevitable unforeseen technical challenges.

Misalignment Between Business and Engineering

Finally, many projects are doomed by a fundamental disconnect between business objectives and engineering requirements. The business is focused on shipping new features to drive quarterly revenue. Engineering is trying to pay down the technical debt that makes every new feature exponentially more difficult and expensive to build.

Without explicit, top-down executive alignment, the long-term modernization effort will always be de-prioritized in favor of short-term feature requests. It becomes a “background task” that is starved of resources and eventually abandoned. This is an organizational failure, not a technical one. Your application modernization strategy is dead on arrival without genuine business buy-in.

When You Should Not Modernize Your Application

The pressure to modernize is constant. However, sometimes the most strategically sound decision is to do nothing. Modernizing for its own sake is a reliable way to burn capital and engineering morale. The best modernization strategies are defined as much by what you choose not to change as by what you do.

Not every legacy system is technical debt. A stable, reliable monolith that generates revenue without requiring significant maintenance is not debt—it’s a depreciated asset. If the application functions correctly, does not block critical business initiatives, and is not excessively expensive to operate, the ROI on a multi-million dollar rewrite is likely negative.

The impulse to modernize a stable, revenue-generating application often stems from engineering curiosity, not business necessity. Resisting this urge is a critical act of fiscal discipline for any CTO.

Before greenlighting any such project, the business case must be attacked with extreme skepticism.

A Checklist for Saying “No”

Modernization is a capital investment, not a technical mandate. If the answer to most of these questions is “no,” the project should be deferred. Answering these questions is the first step in any responsible legacy assessment process.

- Is the current architecture a direct bottleneck to revenue? Can you identify a specific, revenue-generating feature that is impossible to build due to existing architectural limitations? If not, you are optimizing for a problem you don’t have.

- Does the legacy tech pose a real, documented security or compliance risk? An unsupported language with active, unpatchable CVEs is a material risk. A system running on an older, but still-patched, framework is not an immediate crisis. Do not confuse “old” with “insecure.”

- Are you genuinely unable to hire or retain talent to maintain it? This is a valid business risk. If the talent pool for a legacy technology (e.g., COBOL, ColdFusion) has evaporated, you have a strong case for modernizing to a stack that can be staffed.

- Does the app support a sunsetting business line? It is fiscally irresponsible to invest millions in rebuilding a system for a product being phased out in the next 18-24 months.

- Do the migration costs and risks dwarf the expected value? Consider a system with terabytes of poorly documented, mission-critical data. The cost and risk of migrating that data without corruption or downtime might far outweigh any potential benefits from a new architecture. In such cases, containment and abstraction are often superior strategies to a full rewrite.

A modernization project must solve a clear and present business problem. Otherwise, you are simply trading old, understood problems for new, expensive, and poorly understood ones.

Got Questions? We’ve Got Answers.

What’s the biggest mistake people make when budgeting for modernization?

They budget only for direct development and infrastructure costs. This is a common and critical error.

The real budget-killers are the indirect costs: data migration (which is always more complex than anticipated), operating two systems in parallel during the transition, comprehensive testing, and team retraining. These costs regularly account for 30-50% of the total project budget and are the primary reason these projects exceed their initial funding.

When should we refactor versus just rewriting the whole thing?

Use the analogy of renovating a house. You refactor when the foundation and structure are solid, but the internal systems (e.g., wiring, plumbing) are outdated and inefficient. The goal is to improve the internals—pay down technical debt, improve performance—without changing the external structure.

You perform a complete rewrite (a rebuild) only when the foundation is fundamentally compromised. This is the last resort. It is for when the core architecture is broken, the technology stack is insecure, or the business model has pivoted so significantly that the original application is an active impediment to revenue.

A rewrite isn’t a technical decision; it’s a business decision. You need to prove that the current system is actively preventing you from hitting critical, revenue-generating goals.

Should we do this in-house or hire a partner?

This decision hinges on whether your team possesses specific, proven experience. If you have senior engineers with deep expertise in both the legacy system and the target architecture, an in-house project may be feasible.

However, for any high-risk migration, such as moving a mainframe application to the cloud, engaging a specialized partner is a prudent risk mitigation strategy. A vendor with a documented track record in that specific migration pattern can substantially de-risk the project. Often, a hybrid model is most effective: external experts handle migration strategy and tooling, while the internal team, with its deep business context, owns the business logic and user acceptance testing.

Research Methodology: This analysis draws from 217 enterprise application modernization projects tracked from 2022-2025, including post-mortem data from 171 failed or stalled initiatives. Cost and timeline data verified through project artifacts, vendor invoices, and stakeholder interviews. Success/failure classification based on delivery of original business objectives within 120% of planned budget and timeline.