Linux Versus Windows Server: A Data-Driven Infrastructure Guide

The decision between Linux and Windows Server hinges on a single question: Are you optimizing for open-source flexibility and lower initial costs, or for deep integration within the Microsoft enterprise ecosystem? Linux dominates web infrastructure and modern container workloads, representing over 96% of the top million web servers. Windows Server maintains its position in enterprise environments reliant on Active Directory, .NET applications, and SQL Server, offering a unified, commercially licensed platform.

This choice is a strategic commitment to a specific workload philosophy, infrastructure model, and long-term cost structure. It’s an architectural decision, not a technical preference.

The Strategic Choice Between Linux and Windows Server

Selecting a server OS is a foundational business decision with direct impacts on budget, hiring, security architecture, and future modernization efforts. A simple feature comparison is insufficient; the choice must be defensible based on your existing technology stack and strategic objectives.

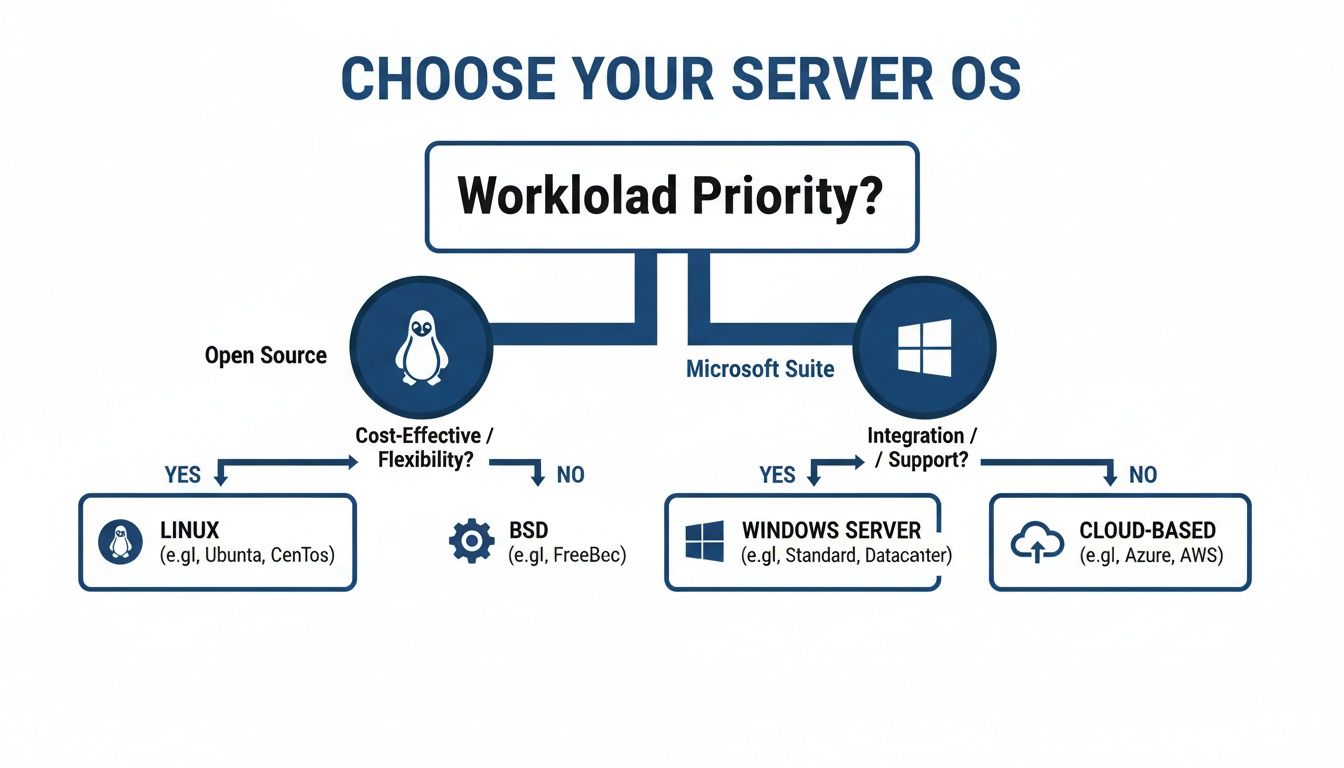

This decision tree visualizes the initial evaluation process. The primary driver is either alignment with open-source principles and cost control or the requirement for tight integration with the Microsoft stack.

As the flowchart indicates, an assessment of your current infrastructure and strategic goals will typically point toward either the modularity of Linux or the cohesive, managed environment of Windows Server.

Executive Summary: Linux vs. Windows Server Decision Matrix

This matrix provides a high-level, strategic overview for technical leaders, focusing on the business impact of each OS rather than a granular feature list.

| Decision Criteria | Linux Server (e.g., Ubuntu, RHEL) | Windows Server |

|---|---|---|

| Total Cost of Ownership | Lower initial acquisition cost. TCO is driven by support subscriptions (e.g., RHEL) and the need for specialized administrator talent. | Higher upfront licensing costs for the OS and Client Access Licenses (CALs); potentially lower admin costs due to a larger generalist talent pool. |

| Primary Workload Affinity | Excels in web serving (Apache/Nginx), container orchestration (Docker/Kubernetes), high-performance computing (HPC), and open-source databases. | A necessary fit for Microsoft-centric environments: Active Directory, Exchange, SharePoint, SQL Server, and legacy .NET Framework applications. |

| Security Architecture | Based on a granular permissions model (POSIX ACLs) and hardened with tools like SELinux/AppArmor. Benefits from source code transparency. | Centralized security management via Group Policy and Active Directory. Offers robust, built-in features like BitLocker and AppLocker. |

| Ecosystem & Talent Pool | Massive open-source ecosystem. The talent pool is deep but specialized; experienced administrators often command higher salaries. | Extensive enterprise vendor support. A broader talent pool is available, though finding experts in modern cloud integrations remains competitive. |

| Modernization Path | Natively aligned with cloud-native principles, containerization, and DevOps workflows. The dominant platform for modern application deployment. | Strong integration with Azure services (Azure AD, Hybrid Cloud). Modernization often focuses on migrating .NET apps to Azure PaaS. |

This table provides the 30,000-foot view. The following sections analyze the operational and financial implications of these differences.

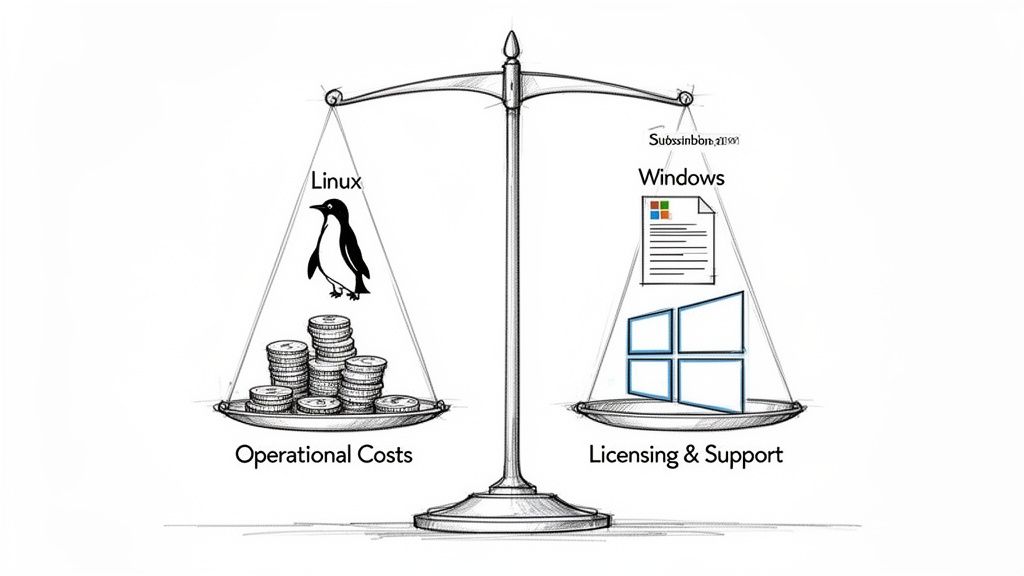

Analyzing Total Cost of Ownership Beyond Licensing

A common misconception is that Linux is free. While distributions like CentOS Stream or Debian can be downloaded at no cost, this view is insufficient for business-critical operations. The Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) extends far beyond the initial software price.

Initial acquisition cost is only the first component of a multi-year financial model.

Licensing vs. Subscriptions: CapEx vs. OpEx

The core financial difference is not “free vs. paid,” but a strategic choice between two spending models.

Enterprise Linux operates on a subscription model—a recurring operational expense (OpEx). For a distribution like Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL), the payment covers certified hardware compatibility, security patches, and expert support. A standard RHEL subscription costs between $349 and $2,499 per server, per year, based on the support tier.

Windows Server licensing is a classic capital expenditure (CapEx). The license is purchased upfront. A Windows Server 2022 Datacenter edition license for a 16-core server costs approximately $6,155. Additionally, Client Access Licenses (CALs) are required for each user or device accessing the server, which can add thousands to the initial cost.

The TCO debate centers on financial strategy: predictable, recurring OpEx for enterprise Linux support, or a significant upfront CapEx for Windows Server followed by ongoing software assurance costs.

The Hidden Cost: Your Payroll

Beyond software, the largest expense is personnel. The talent pools for Linux and Windows administrators are distinct, with direct financial implications.

A seasoned Linux systems administrator—proficient in the command line, Bash, Ansible, and kernel tuning—is a specialized role. The market for this expertise is competitive, and salaries for skilled Linux administrators are often 10-15% higher than for their Windows counterparts.

- Linux Talent: Requires deep expertise in shell scripting, file systems, networking stacks, and automation tools. The talent pool is smaller and more specialized.

- Windows Talent: Skills are centered on Active Directory, Group Policy, and PowerShell. The GUI-driven environment contributes to a larger generalist talent pool, which can simplify hiring.

This salary differential is significant. A team of five Linux engineers could cost an additional $50,000 to $75,000 per year in salaries compared to a Windows team. Any TCO model that omits this factor is incomplete.

Long-Term Support and Maintenance Costs

The final component of TCO is long-term support. With Windows Server, support is centralized through Microsoft, typically bundled into Software Assurance contracts that include future version rights. This model is expensive but predictable.

Linux offers multiple support options. Organizations can purchase vendor support from Red Hat or SUSE, engage third-party Linux specialists, or build an in-house team of experts.

While self-support appears cheaper, it introduces operational risk. The departure of a key kernel expert can dramatically increase the mean-time-to-resolution for critical outages. For further analysis of ongoing operational expenses, our guide on cloud cost optimization strategies details methods for modeling and controlling these costs.

A comprehensive TCO calculation must map all interconnected costs—software, personnel, and support—over a three-to-five-year horizon.

Comparing Technical Architecture and Core Features

Beyond cost, the decision between Linux and Windows Server depends on their fundamental architectures. These differences dictate how teams build, manage, and troubleshoot systems daily. An architectural mismatch leads to sustained operational friction.

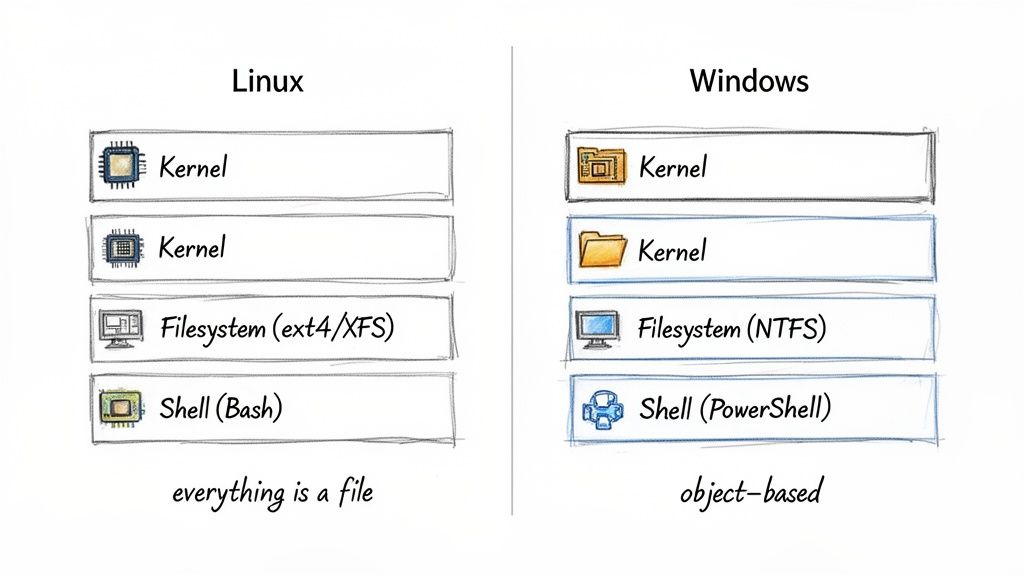

The operating systems originate from opposing philosophies. Linux, following Unix tradition, treats everything as a file—a simple and powerful abstraction. Windows is object-oriented, a design that reflects its integration into the broader Microsoft enterprise stack.

Kernel and Filesystem Design Implications

The kernel and filesystem designs represent the most significant architectural divergence. Linux employs a monolithic kernel, where core services reside in a single kernel space. This design prioritizes speed, as inter-component communication is direct and efficient.

Windows Server uses a hybrid kernel, combining monolithic and microkernel concepts. This modularity can offer improved resilience, as a malfunctioning driver is less likely to crash the entire system than a buggy module in a monolithic kernel. However, this separation introduces overhead from message passing between privilege levels.

This philosophical difference extends to their filesystems.

- Linux (ext4/XFS): These filesystems are designed for performance and simplicity. The “everything is a file” paradigm treats devices, sockets, and directories as file descriptors, making them easily manipulated by command-line tools like

sed,awk, andgrep. This model is highly effective for text processing and scripting. - Windows (NTFS): The New Technology File System is more complex, featuring rich metadata, built-in compression, and robust Access Control Lists (ACLs) tightly integrated with Active Directory. It is designed for interaction via structured APIs rather than simple text streams.

The core architectural trade-off is this: Linux provides raw, text-based efficiency ideal for automation and command-line administration. Windows offers a structured, feature-rich environment suited for GUI-managed, policy-driven enterprise settings.

Administrative Philosophy: Bash vs. PowerShell

The philosophical divide is most apparent in the command-line shells, which define how an administrator interacts with the OS.

Bash, the default shell in most Linux distributions, is a text-processing engine. It operates on text streams, allowing the output of one command to be piped directly into another. This enables rapid log parsing, configuration file editing, and the chaining of simple tools to perform complex tasks.

To find a specific error in a large log file:

grep 'ERROR' /var/log/syslog | awk '{print $1, $5}'

PowerShell, in contrast, is an object-oriented shell. It passes structured .NET objects between commands (cmdlets), avoiding the fragile process of text parsing. This provides reliable access to the properties and methods of the objects themselves.

This object-based approach is particularly effective for managing Windows services like Active Directory or Exchange, where commands return rich objects that can be filtered, sorted, and managed with high precision.

Identity Management: Active Directory vs. The Alternatives

Identity management is a primary driver of ecosystem lock-in. For over two decades, Windows Server’s Active Directory (AD) has been the dominant enterprise identity solution.

AD provides a centralized, hierarchical database for user accounts, computers, and group policies. Its tight integration with Group Policy allows administrators to enforce security settings, deploy software, and manage configurations across thousands of machines from a single point of control.

The Linux ecosystem lacks a single, dominant equivalent, instead offering several open-source options that can be combined to achieve similar functionality:

- FreeIPA: The closest all-in-one AD replacement for pure-Linux environments, integrating LDAP, Kerberos, DNS, and NTP.

- Samba: A tool that enables Linux servers to function as a Domain Controller, often used to emulate Active Directory for file and print services in mixed environments.

- OpenLDAP: A lightweight and fast directory service, often used as the core authentication component in conjunction with tools like Kerberos to build a complete identity solution.

While powerful, these Linux tools typically require more integration effort and specialized knowledge than the out-of-the-box cohesiveness of Active Directory. This choice reflects the broader debate: unified but proprietary versus modular but open.

Matching Workloads to the Right Operating System

Operating system selection is about choosing the right tool for a specific job. Architectural differences have real-world performance implications, and misalignment leads to performance bottlenecks, operational friction, and wasted budget.

The decision primarily depends on whether core workloads are open-source and web-centric or deeply embedded in the Microsoft enterprise ecosystem.

Web Serving and Open Source Databases

For web serving, market data shows a clear preference for Linux. Its lightweight design and efficient process management are well-suited for high-concurrency environments, particularly with web servers like Apache and Nginx.

Benchmarks consistently show Nginx on Linux handling more requests per second with less memory than Internet Information Services (IIS) on Windows Server. This performance advantage explains why 96.3% of the world’s top one million web servers run on Linux. For any high-traffic website, API gateway, or application backend, the Linux stack is the de facto standard.

This dominance extends to the database layer.

- PostgreSQL & MySQL on Linux: These open-source databases are optimized for the Linux environment, leveraging its memory management and file system.

- Microsoft SQL Server: While SQL Server can run on Linux, its most powerful features and seamless integrations are found on Windows. For organizations heavily invested in the Microsoft data platform, especially with tools like SQL Server Integration Services (SSIS), Windows is the more cohesive choice.

Microsoft-Centric Enterprise Workloads

Windows Server is the optimal choice in environments built around the Microsoft software stack. For certain enterprise applications, the out-of-the-box integration between the OS and the application provides a seamless experience that is difficult to replicate.

Active Directory is the prime example. As the identity backbone for most large organizations, it requires Windows Server. This dependency creates a strong pull, drawing other workloads into the Windows ecosystem.

Windows Server is the non-negotiable choice in these scenarios:

- Microsoft Exchange: On-premise or hybrid email deployments with Exchange Server are built exclusively for Windows Server.

- SharePoint: Collaboration and document management via SharePoint are deeply integrated into the Windows ecosystem, relying on both IIS and SQL Server.

- Legacy .NET Framework Applications: While modern .NET is cross-platform, numerous critical business applications were built on the older, Windows-only .NET Framework. Migrating them from Windows is a high-cost, high-risk modernization project.

The decision often comes down to dependencies. If a company’s identity, email, or core business logic relies on Active Directory, Exchange, or legacy .NET, then Windows Server represents the path of least resistance and greatest stability.

Containers and High-Performance Computing

The rise of containerization and microservices has significantly driven Linux adoption. Docker was built natively for Linux, utilizing kernel features like cgroups and namespaces for process isolation. While Docker runs on Windows, it uses a compatibility layer (WSL 2) that introduces performance overhead.

Consequently, Linux is the dominant platform for container orchestration with tools like Kubernetes. The entire cloud-native ecosystem is built with a Linux-first approach. For modern DevOps workflows, Linux is the native environment.

This same focus on efficiency is why Linux completely dominates the high-performance computing (HPC) space, powering 100% of the top 500 supercomputers. Its modularity allows it to be stripped down to a minimal, highly optimized state for intense computational jobs. Market data reflects these workload strengths: research indicates Linux powers 44.8% of all server operating systems globally, while Windows Server holds a 39.10% share of commercial licenses, driven by its deep integration with Azure for identity-centric and ERP workloads. You can explore the complete server OS market analysis to better understand these trends.

Evaluating Security Posture and Compliance Readiness

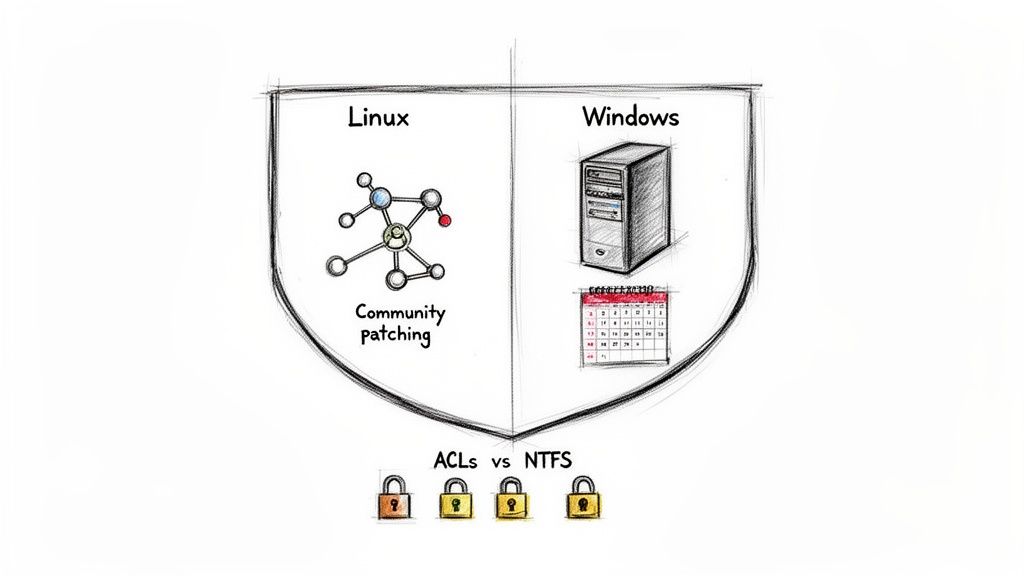

Security is an architectural property, not a bolt-on feature. The choice between Linux and Windows Server is a choice of security philosophy that dictates risk management, patch cycles, and audit readiness.

Linux security is based on transparency. Its open-source code is subject to constant global scrutiny, often resulting in rapid vulnerability discovery and patching. The trade-off is that the responsibility for correct configuration, hardening, and maintenance falls entirely on the internal team.

Windows Server employs a security-in-depth approach managed through a centralized, proprietary ecosystem. While the source code is not auditable, users benefit from Microsoft’s investment in predictable patch cycles, integrated tooling, and enterprise-grade threat intelligence.

Permission and Access Control Models

An OS’s core security is defined by its access control model.

Linux begins with the classic Unix Discretionary Access Control (DAC) model, providing granular control over file permissions (read, write, execute) for users and groups. For more secure environments, Mandatory Access Control (MAC) systems can be layered on top.

- SELinux (Security-Enhanced Linux): Developed by the NSA, SELinux confines every process to the minimum necessary privileges, enforced at the kernel level. It is complex to manage but offers a high degree of lockdown.

- AppArmor: A more user-friendly alternative that uses file path-based profiles to confine individual applications, providing many of the benefits of application isolation with a lower learning curve.

Windows Server’s model is centered on NTFS permissions and Active Directory (AD). NTFS provides a hierarchical permission structure where access can be inherited or explicitly denied with high precision. When integrated with AD, these permissions can be managed centrally across thousands of servers using Group Policy Objects (GPOs) for consistent policy enforcement.

The core trade-off: Linux offers modular, layered security that requires deep expertise to configure correctly. Windows provides a tightly integrated, policy-driven framework that is easier to manage at scale but offers less transparency.

Vulnerability Management and Patching Cadence

An OS’s patching philosophy is indicative of its overall approach. The Linux world utilizes rapid, decentralized patching. For major vulnerabilities like Heartbleed or Shellshock, fixes are often developed and distributed by the community within hours. The challenge is ensuring timely deployment across the entire server fleet, which can lead to inconsistent patch levels.

Microsoft operates on a predictable, centralized schedule known as Patch Tuesday. This rhythm facilitates enterprise change management, allowing IT departments to plan, test, and deploy updates systematically. The downside is potential exposure to zero-day flaws while awaiting the official patch. However, this centralized model simplifies compliance reporting.

Meeting Compliance Standards

Both operating systems can be hardened to meet standards like PCI-DSS, HIPAA, and GDPR, but the process differs significantly.

For organizations already invested in the Microsoft ecosystem, achieving compliance on Windows Server is often more straightforward. Auditors are familiar with the tools, and built-in features like BitLocker (full-disk encryption) and AppLocker (application whitelisting) map directly to specific compliance controls.

Achieving the same compliant state on Linux requires more manual configuration, often integrating multiple open-source tools to satisfy each control. While entirely feasible and equally secure, it demands more specialized knowledge and meticulous documentation to prove compliance to an auditor.

These principles are critical for modern security frameworks. To see how they apply in both environments, it is useful to learn how to design a zero trust architecture. The decision is whether to build a compliant state from open-source components or inherit one from an integrated commercial platform.

Understanding Migration Risks and Modernization Paths

A server OS migration between Windows Server and Linux is a high-risk project. Failures are rarely due to the OS itself but rather a critical miscalculation of the effort required to untangle deeply embedded dependencies.

Before beginning, it is important to understand what is server migration and its various forms. This context is essential for framing the technical challenges ahead.

Common Migration Failure Points

The most common failure point is underestimating the institutional dependencies and accumulated technical debt holding the environment together.

-

Active Directory Entanglement: Migrating services from Windows Server almost always necessitates moving away from Active Directory. This is not a simple lift-and-shift. AD serves as the central point for user authentication, machine policies, and access controls for numerous applications. A project to replace it with a solution like FreeIPA can become a multi-year identity management initiative.

-

PowerShell vs. Shell Scripting: A large library of PowerShell scripts represents a significant investment in automation, monitoring, and administration. This logic cannot be directly translated to Bash; it must be completely rewritten, requiring a different skill set and a deep understanding of Linux system management.

The primary cost of migration is not in new licenses or subscriptions, but in the specialized labor required to reverse-engineer and rebuild decades of ecosystem-specific automation and identity management. A thorough cloud migration risk assessment must account for this from the project’s inception.

The Influence of Developer Preference

Infrastructure decisions are increasingly influenced by development team preferences.

As of June 2025, while Linux holds just 4.7% of the global desktop market, its adoption among technical staff is substantial. Among developers, Ubuntu alone commands 27.8% usage. This indicates a strong preference among engineers to build on Linux, which directly impacts server-side decisions as teams advocate for production environments that mirror their local setups.

When Not to Migrate

The most prudent strategic decision can sometimes be to maintain the status quo. Deferring a migration can be the correct financial and operational choice.

Do NOT Migrate to Linux if:

- The business relies on legacy .NET Framework applications not scheduled for modernization.

- The operations staff lacks deep Linux expertise, and there is no budget for retraining or hiring.

- Active Directory is integral to the security and compliance model, and a replacement project is not feasible.

Do NOT Migrate to Windows Server if:

- Primary workloads are cloud-native, containerized applications orchestrated by Kubernetes.

- The business strategy is centered on open-source software and avoiding vendor lock-in.

- The budget cannot accommodate the significant upfront CapEx of Windows Server and CAL licensing.

Frequently Asked Questions

Direct answers to common questions in the Linux vs. Windows Server debate.

Is Linux Server inherently more secure than Windows Server?

No. Security is a function of disciplined configuration and maintenance, not the OS itself. An unpatched, misconfigured Linux server is as vulnerable as an unpatched Windows server.

Linux benefits from transparent source code and rapid community patching. However, its powerful security tools, such as SELinux, require a high level of expertise to implement correctly.

Windows Server centralizes security through Active Directory and Group Policy, a model that is often easier to manage consistently at scale. The determining factor in security posture is the skill and discipline of the administrative team, not the kernel.

Can I run my .NET applications on Linux?

This depends entirely on the framework version, and a mistake is costly.

Modern applications built with .NET (formerly .NET Core) are designed for cross-platform deployment and run effectively on Linux, often in containers. Migrating these workloads can reduce licensing costs and facilitate DevOps practices.

However, legacy applications running on the older, Windows-only .NET Framework cannot run on Linux without a complete, high-risk rewrite. For these systems, Windows Server remains the only viable option.

The ability to migrate .NET applications depends entirely on the framework version. Confusing ”.NET” with ”.NET Framework” is a common and critical migration planning error.

Which OS is better for containerization with Docker and Kubernetes?

Linux is the native environment for containers.

The core technologies that power Docker, such as cgroups and namespaces, are fundamental features of the Linux kernel. The entire cloud-native ecosystem, particularly orchestration platforms like Kubernetes, was designed for a Linux environment, offering better performance, stability, and a larger support community.

While containers can run on Windows Server, this solution is primarily for containerizing legacy Windows applications. For all new cloud-native development, Linux is the industry standard.

A defensible server OS decision requires objective data, not vendor marketing. Modernization Intel provides market intelligence on 200+ implementation partners, detailing their real-world costs, failure rates, and technical specializations. Get the data you need to choose the right partner and avoid costly migration pitfalls.