Static vs Dynamic Code Analysis: A Guide for Technical Leaders

The core difference between static vs. dynamic code analysis is execution. One examines blueprints, the other stress-tests the finished structure. Choosing the wrong one for the job introduces predictable, and avoidable, risk.

Static Application Security Testing (SAST) is a white-box methodology. It analyzes source code, bytecode, or binaries before runtime. The objective is to identify insecure coding patterns, dependency vulnerabilities, and systemic design flaws from an “inside-out” perspective.

Dynamic Application Security Testing (DAST), in contrast, is a black-box methodology. It has no access to source code. It tests a running application by sending payloads and analyzing responses, looking for runtime failures and environment-specific vulnerabilities that only manifest during execution.

A High-Level Comparison of Analysis Methods

For any technical leader, the first step in making a defensible tooling decision is grasping the core trade-offs between SAST and DAST. Each one mitigates a different class of risk at different stages of the software development lifecycle (SDLC). The goal is not to determine which is “better,” but which is appropriate for a specific context.

Static analysis is analogous to a structural engineering review of skyscraper blueprints. It examines raw architectural plans—the source code—to find weaknesses before construction begins. This approach is effective at catching design flaws early, which is when they are least expensive to remediate. An IBM report found a defect fixed in production can be up to 100 times more expensive than one caught during the design phase.

Dynamic analysis is more like a post-construction building inspection. It tests how the structure performs under real-world load—running plumbing, operating elevators, and activating fire suppression systems. This is the only method for finding issues that arise from the interaction of discrete components or environmental configurations.

SAST vs DAST At a Glance

The following table outlines the critical differences for engineering leaders evaluating SAST and DAST tools.

| Criterion | Static Analysis (SAST) | Dynamic Analysis (DAST) |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis Type | White-box (examines source code) | Black-box (tests running application) |

| When to Use | Early SDLC (coding, commit, build) | Late SDLC (QA, staging, production) |

| Code Access | Requires direct source code access | Does not require source code |

| Typical Findings | SQL injection, buffer overflows, insecure coding | XSS, authentication flaws, server misconfigs |

| Speed | Fast; integrates directly into CI pipelines | Slower; needs a fully deployed environment |

| Code Coverage | Can analyze 100% of the codebase | Limited to executed paths and user flows |

| False Positives | Higher rate; often requires significant tuning | Lower rate; findings are more actionable |

SAST provides broad coverage inside the codebase. DAST provides high-fidelity findings from an external attacker’s perspective. They are not mutually exclusive; they address different aspects of application security.

How Static Analysis Finds Flaws Before You Even Run The Code

Static analysis examines the design of an application—the source code, bytecode, or binaries—to find structural weaknesses before runtime. This pre-execution check is the fundamental differentiator in the static vs. dynamic code analysis comparison.

The process begins by building a model of the application’s structure. The tool creates an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) to map the code’s grammar and a Control Flow Graph (CFG) to outline all possible execution paths. These models create a comprehensive map of the software’s internal logic.

Using this map, the tool can trace data flows, evaluate logical branches, and check for violations of predefined security rules or coding standards.

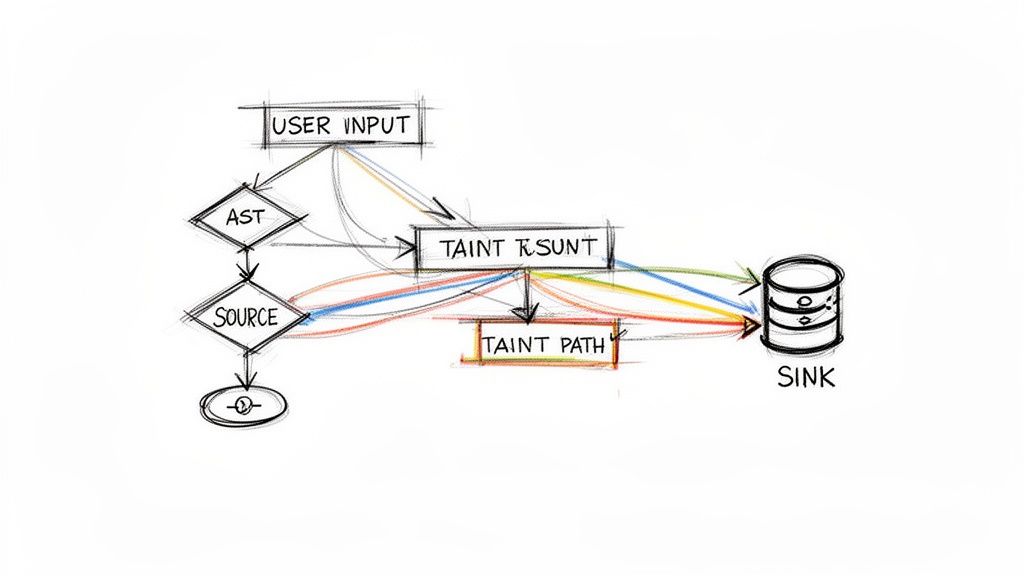

Uncovering Hidden Dangers with Taint Analysis

A core technique in SAST is taint analysis. It tracks untrusted user data as it flows through an application to determine if it reaches a sensitive operation, or “sink,” without proper sanitization.

The process involves three steps:

- Identify the Source: The tool flags entry points where external, untrusted data can enter the system, such as user input fields or API parameters. This data is marked as “tainted.”

- Trace the Path: The analyzer follows the tainted data through all possible code paths as it moves between variables, functions, and modules.

- Locate the Sink: The tool searches for sinks—sensitive operations like a database query function—where tainted data could cause harm.

If the tool identifies an unsanitized path from a source to a sink, it flags a potential vulnerability like SQL injection. This method is effective for catching entire classes of injection flaws before code enters a test environment.

Taint analysis is particularly important for legacy modernization projects. We’ve observed it uncover deeply buried flaws where a decades-old COBOL batch process writes data that is later consumed by a new Java API, creating an attack vector that manual review would likely miss.

Proving Vulnerabilities with Symbolic Execution

Another, more computationally intensive technique is symbolic execution. Instead of testing with concrete values like username = "testuser", this method uses symbolic values (mathematical variables) to represent all possible inputs.

This allows the tool to explore all execution paths simultaneously. It solves a series of mathematical constraints to determine which inputs would force the program down a specific path, uncovering edge cases that manual testing could miss. By doing this, symbolic execution can mathematically prove whether certain conditions, like a buffer overflow, are possible. For more on how internal code structure impacts risk, see our analysis on coupling and cohesion in legacy code.

This depth of analysis is why the static analysis market was valued at USD 1.1 billion in 2022. It’s projected to grow at a 14% CAGR through 2032, driven by increasing software complexity. Cloud-based SAST tools accounted for 50% of market share in 2022, offering the scalability required for large-scale modernization efforts. The full static analysis market report has more data.

How Dynamic Analysis Uncovers Runtime Failures

If static analysis reviews blueprints, dynamic analysis stress-tests the completed building. It interacts with the live application as a “black-box,” simulating real users and attackers to find failures that only manifest during execution.

A common technique is fuzzing, which involves sending a high volume of unexpected, malformed, or random data to application inputs like API endpoints or login forms. The goal is to induce a crash, error state, or security flaw that only appears under operational stress.

This real-world testing model is designed to find a class of vulnerabilities that static scans cannot detect.

Finding Flaws That Only Appear in a Live Environment

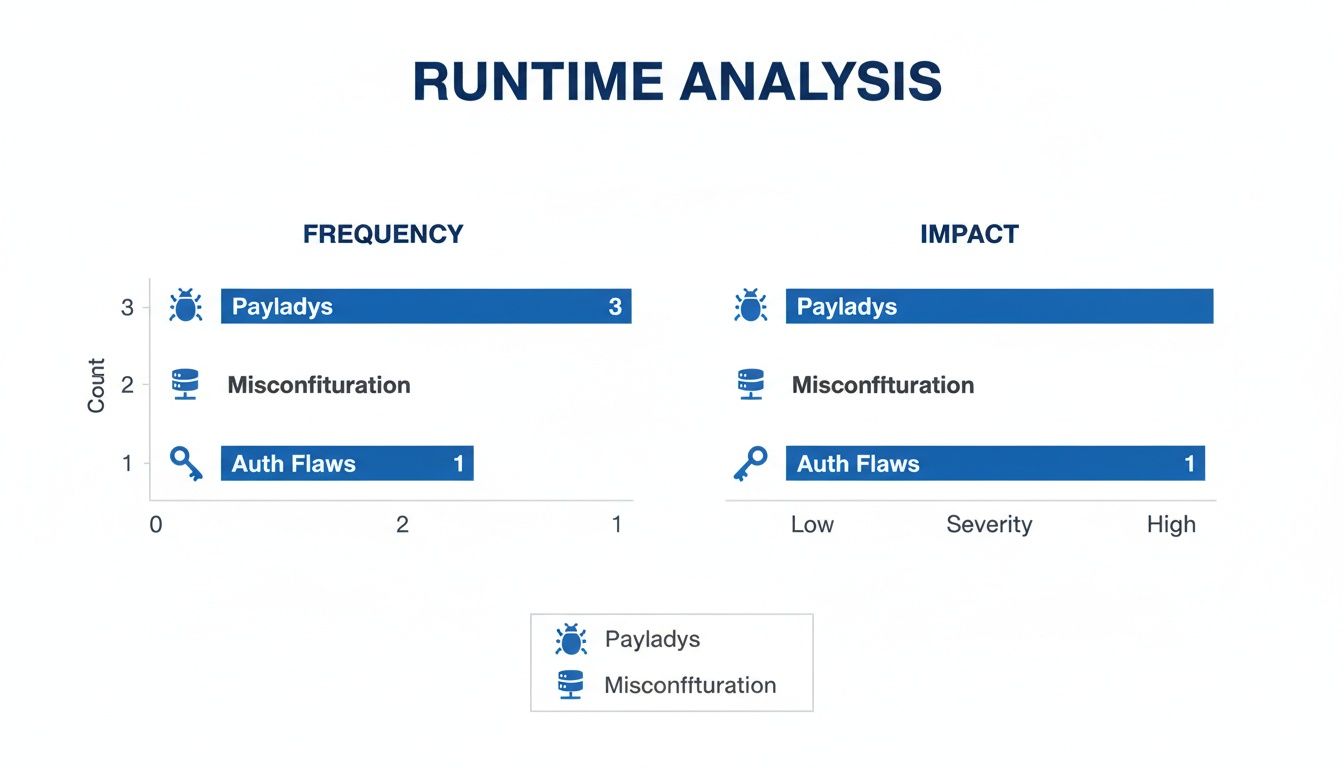

Dynamic analysis excels at identifying issues tied to the runtime environment, application state, and user interaction—factors a static scan is blind to.

Key areas where Dynamic Application Security Testing (DAST) is effective:

- Authentication and Session Management Flaws: DAST can test if session tokens are predictable, if logging out terminates a session correctly, or if a user can escalate privileges post-authentication. These are behavioral, not syntactical, issues.

- Server and Configuration Issues: It identifies environmental defects like exposed directory listings, improper HTTP security headers, or verbose error messages that leak internal system information. These are operational misconfigurations, not code-level flaws.

- Cross-Site Scripting (XSS): By injecting test scripts and observing the application’s response, DAST can confirm if user inputs are rendered without sanitization—a classic runtime vulnerability.

Proper application of these techniques requires specialized tools. Our guide on DAST security tools like OWASP Zap provides an overview of available engines for automating these attack patterns.

A critical blind spot for static analysis is its inability to evaluate third-party components where source code is unavailable. Dynamic analysis treats these components as black boxes, testing their behavior and integration points just like any other part of the live application.

The Limitation of Code Coverage

The primary trade-off with dynamic analysis is that it can only test what it can reach. If a feature is located deep within the UI or requires a complex sequence of user actions to access, a DAST tool may never discover it, leaving that code untested.

Achieving high code coverage with DAST requires a comprehensive suite of integration tests and user scripts to guide the scanner through all critical workflows. Without this, vulnerabilities in less-trafficked parts of an application may remain undetected.

This is a central point in the static vs. dynamic code analysis debate. Static analysis can, in theory, cover 100% of the codebase. Dynamic analysis coverage is directly proportional to the quality and breadth of test cases. For mission-critical systems, relying on one method creates significant gaps. This is a point we emphasize in our guide on automated testing for migrated applications.

This need for comprehensive testing is driving investment in the market. The static code analysis software market is projected to grow at a 14.5% CAGR through 2031, fueled by the adoption of DevOps and Agile methodologies. A report from The Insight Partners on the market indicates a clear trend: both static and dynamic tools are necessary to secure modern software.

Technical Tradeoffs: SAST vs. DAST

The decision between static and dynamic analysis must go beyond definitions to include metrics like speed, accuracy, and scope. These factors directly impact budget, engineering time, and release velocity.

SAST is designed for speed and developer integration. It scans source code, allowing it to be integrated directly into a CI/CD pipeline to provide feedback within minutes of a commit. This “shift left” approach aims to catch flaws early when remediation costs are lowest. However, this speed often comes at the cost of accuracy.

DAST operates on a running application, which is inherently slower. A comprehensive scan can take hours, requiring a fully configured test environment. This makes DAST better suited for later stages of the SDLC, such as QA or staging, rather than for immediate feedback on individual code changes.

Accuracy and The False Positive Problem

A significant operational challenge with SAST tools is their high rate of false positives. Lacking runtime context, they cannot always distinguish between a theoretical vulnerability and an exploitable one. A SAST tool might flag a code pattern as dangerous even if it is unreachable or neutralized by another control.

Even well-tuned commercial SAST tools can have a false positive rate of 5-10%. Out of the box, this rate can be much higher. This creates a risk of “alert fatigue,” where developers begin to ignore the tool’s output, reducing its ROI.

DAST findings, by contrast, are typically high-fidelity. If a DAST tool reports a vulnerability, it is because it successfully exploited it. This provides actionable feedback, reducing the time engineering teams spend investigating non-issues.

The core difference is proof. SAST suggests, “This line of code could be a problem.” DAST demonstrates, “An exploit attempt on this endpoint was successful.”

Scope and What Gets Missed

Static analysis has one significant advantage in scope: it can scan 100% of a codebase, including obscure functions and legacy code that is rarely executed. For compliance mandates or identifying deep architectural flaws, this exhaustive coverage is necessary.

DAST’s scope is narrower. It can only test parts of the application exercised during a scan. If automated tests or manual processes do not trigger a specific feature, any vulnerabilities in that code remain undiscovered. Effective DAST coverage depends on a mature and thorough testing strategy. For more on the impact of live environments, see our guide on observability in modernized systems.

DAST excels at finding runtime issues that SAST is blind to, such as configuration errors, authentication bypasses, and flaws that emerge from service interactions.

As the dashboard shows, DAST is built to find issues that are entirely dependent on the application’s live state and environment—factors a static analysis tool cannot comprehend.

Quantitative Comparison of SAST vs DAST

This table breaks down key performance and operational metrics for evaluating these tools in an engineering context.

| Metric | Static Analysis (SAST) | Dynamic Analysis (DAST) | CTO’s Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feedback Speed | Minutes (integrated into CI) | Hours (requires test environment) | SAST supports fast dev cycles. DAST is for pre-release validation. |

| False Positive Rate | High (5-10% after tuning) | Very Low (<1%) | High SAST noise can kill developer adoption. DAST findings are trusted. |

| Code Coverage | 100% of the codebase | Limited by test execution paths | SAST is essential for compliance. DAST coverage depends on test quality. |

| Setup Complexity | Low to Medium (CI plugin) | High (requires stable test env) | SAST is easier to pilot. DAST is a significant infrastructure commitment. |

| Remediation Context | Precise (exact file and line number) | Indirect (symptom, not root cause) | SAST makes fixing easy. DAST requires investigative work from developers. |

| Environment Needs | None (scans source code) | Production-like Environment | The cost and effort of maintaining a DAST environment is a major TCO factor. |

The decision is not about which tool is superior, but which tool addresses the right risk at the right stage of the development lifecycle.

Cost of Remediation and Operational Overhead

The total cost of ownership extends beyond licensing fees.

-

SAST Remediation: The cost per bug is reduced by early detection but inflated by the engineering hours required to triage false positives. When a true positive is found, remediation is typically fast, as the tool points to the exact line of code.

-

DAST Remediation: DAST provides definitive proof of a vulnerability but often cannot identify the flawed code’s location. A developer must work backward from the symptom (e.g., a successful SQL injection) to find and fix the root cause.

Setup complexity is another factor. Integrating a SAST tool into a CI pipeline is a well-defined task. Deploying DAST effectively requires building and maintaining a stable, high-fidelity test environment that mirrors production—a significant operational commitment.

When to Use Static, Dynamic, or Both

The static vs. dynamic code analysis debate is not about selecting a single “best” tool. It is about applying the correct tool for a specific job at the appropriate point in the SDLC. Each approach identifies different categories of flaws.

When to Double Down on Static Analysis (SAST)

SAST is the appropriate choice when the goal is to understand the internal quality and structural integrity of an application before it runs. Its primary advantage is its ability to scan 100% of the codebase.

SAST is necessary in these scenarios:

- Early and Often in Development: Integrate SAST into the CI pipeline to scan code on every commit or pull request. This provides immediate feedback to developers on insecure patterns, preventing flawed code from being merged.

- Compliance and Audits: To demonstrate adherence to standards like MISRA, CERT, or the OWASP Top 10, SAST provides the exhaustive, line-by-line coverage required as evidence that security rules are implemented.

- Architectural Reviews & Modernization: Before a major refactoring or when assessing a legacy system, a deep static scan is invaluable. It identifies systemic design flaws—such as high coupling and cohesion in legacy code—that do not manifest in runtime tests but impede future development.

For large initiatives like Modernizing Legacy Systems, static analysis provides a complete map of the existing code, allowing teams to catalog technical debt and plan a viable transition.

When to Prioritize Dynamic Analysis (DAST)

DAST is used to assess how an application behaves under attack. It answers the question: “Is my running application vulnerable to external threats?”

DAST is the right tool in these situations:

- The Final Pre-Production Gate: Run DAST scans in a staging environment that mirrors production. This is a final check for environment-specific misconfigurations, broken authentication flows, or vulnerabilities that emerge from service interactions.

- Testing Black-Box Components: When using third-party APIs or compiled libraries where source code is unavailable, SAST is ineffective. DAST is the only way to probe these components from the outside to assess their security posture.

- Validating Security Controls: DAST can be used to test the effectiveness of a Web Application Firewall (WAF) or other runtime defenses by simulating real-world attacks to confirm that controls are configured correctly.

A common failure mode we observe is an organization achieving a clean SAST scan and assuming the application is secure. They then deploy it to a misconfigured cloud environment, leaving it vulnerable to runtime attacks that a DAST tool would have detected.

The Hybrid Strategy: Your Most Defensible Position

For most organizations, the static-versus-dynamic debate is a false choice. A layered defense combining both is the most effective strategy.

A robust, combined strategy works as follows:

- SAST at Build-Time: Use static analysis as a quality gate within the CI pipeline to prevent insecure or poorly written code from being merged into the main branch. This maintains the internal security of the codebase.

- DAST at Run-Time: Use dynamic analysis later in the CD pipeline as a final validation step in a production-like environment. This confirms that the fully assembled application can withstand external attacks.

By pairing build-time code analysis with runtime behavioral validation, you can detect a broader range of vulnerabilities, from defects in legacy code to issues introduced by modern integrations. This approach secures the application from both the inside-out and the outside-in, reducing the probability of a vulnerability reaching production.

The Real Cost of Code Analysis (And Why Most Programs Fail)

Calculating the true cost of a SAST or DAST program requires looking beyond the license fee. The real price is paid in engineering hours spent on setup, tuning, and triaging alerts. Many of these programs fail to deliver ROI within the first year, not because of the technology, but because of execution.

Where Code Analysis Initiatives Go to Die

The most common failure modes are related to rollout and adoption, not scanner algorithms.

The same three patterns occur repeatedly:

- The “Turn It On and Pray” Rollout. An organization procures a tool, points it at a codebase, and enables all rules. This immediately triggers alert fatigue. When developers receive thousands of low-confidence warnings, they are more likely to ignore them than fix them.

- Zero Developer Buy-In. If a SAST tool generates a 40% false positive rate (which is not uncommon without tuning), developers begin to view it as an impediment to releases rather than a safety measure. Once their trust is lost, the tool becomes shelfware.

- Legacy Code Blind Spots. A team purchases a scanner that is highly effective for Python and Java, but the project’s goal is to modernize a mainframe. The tool has limited or no support for COBOL or PL/I, rendering it ineffective for the riskiest parts of the system.

The number one predictor of failure is treating code analysis as a security-only problem. If developers perceive the tool as a punitive measure rather than a tool for improvement, the program is unlikely to succeed. The objective must be collaborative improvement, not just compliance.

A successful implementation budget must account for the hours spent tuning rule sets to reduce noise, integrating findings into IDEs for immediate feedback, and establishing a clear triage process. Investing in the process is as critical as paying the license fee.

Got Questions? Here Are the Straight Answers.

When engineering leaders evaluate static vs. dynamic analysis, the same questions arise. This is what you need to know.

Can We Just Pick One and Ditch the Other?

No. Attempting to replace one with the other is a strategic error. They are complementary tools for different jobs.

SAST is an architectural review of your blueprints. It scans 100% of your source code for structural flaws before construction.

DAST is a physical stress test of the finished building. It attacks the running application from the outside to find weaknesses an attacker would exploit.

A clean SAST report indicates that your code is well-structured. A clean DAST report indicates that it can withstand a real-world attack. Both are necessary.

Relying solely on SAST leaves you blind to runtime issues. Relying solely on DAST means a critical flaw could exist in a code path your tests do not trigger.

Where Do SAST and DAST Actually Fit in Our CI/CD Pipeline?

They integrate at different stages of the SDLC by design.

-

SAST (Shift Left): This is a first line of defense. It runs early, either in the developer’s IDE or as an automated check on every commit or pull request in the CI pipeline. The goal is to catch flaws immediately.

-

DAST (Shift Right): This tool is used later, after the application is deployed to an environment like staging or QA. It runs against the live application as part of the Continuous Delivery pipeline to simulate attacks before release.

What’s a Realistic False Positive Rate for SAST?

The rate depends entirely on the tool and the effort invested in tuning it.

Out of the box, some tools can have false positive rates of 30% or higher, which can lead to developers ignoring the results.

A well-configured commercial SAST tool can be tuned down to a more manageable 5-10%. Achieving this requires a deliberate effort to customize rule sets, suppress findings irrelevant to your codebase, and integrate results into developer workflows to simplify triage. Reducing this rate is a critical factor in the success of a SAST program.

At Modernization Intel, we provide unbiased, data-driven intelligence on over 200 implementation partners. We cut through the sales pitches to give you the real costs, failure rates, and technical specialties you need to make a defensible vendor decision. Get your vendor shortlist by exploring our platform at https://softwaremodernizationservices.com.

Need help with your modernization project?

Get matched with vetted specialists who can help you modernize your APIs, migrate to Kubernetes, or transform legacy systems.

Browse Services