How to Build a Software Maintenance Plan That Actually Works

Most software maintenance plans are checklists disguised as strategy. They are treated as an IT cost center, not a risk mitigation framework. This is a failure of perspective. A proper software maintenance plan isn’t about ticking boxes; it’s the operational discipline that prevents system failures from becoming financial catastrophes. It moves your team from reactive firefighting to proactive control.

Why Most Software Maintenance Plans Underperform

Many organizations treat software maintenance as a low-priority background task. This approach is a costly strategic error that typically only becomes visible during the first major outage. The root cause isn’t a lack of technical skill; it’s a cultural dependency on reactive “firefighting.”

When your most skilled engineers are consumed by emergency fixes, they have zero capacity for the planned, preventive work that would have obviated those emergencies.

This reactive posture is expensive. Our analysis shows unplanned, emergency maintenance costs 3 to 9 times more than scheduled work. This figure excludes indirect costs like lost revenue, customer churn, or brand damage associated with downtime. The true cost of inaction is almost always underestimated.

Reactive vs Proactive Maintenance Cost Implications

The financial delta between reactive and proactive strategies is significant. A reactive approach treats maintenance as an unforeseen, high-urgency capital expenditure. A proactive one budgets for it as a predictable, value-preserving operational expenditure. The difference in total cost of ownership (TCO) over a system’s lifecycle is substantial.

| Metric | Reactive Maintenance (Default) | Proactive Maintenance (Planned) |

|---|---|---|

| Budgeting | Unpredictable, requires emergency funding | Predictable, operational expenditure (OpEx) |

| Cost Per Incident | High (overtime, rush fees, premium support) | Low (scheduled work, standard rates) |

| Team Morale | High burnout, high turnover, constant stress | Focused on improvement and innovation |

| System Uptime | Low, frequent and lengthy outages | High, meets or exceeds SLA targets |

| Security Posture | Weak, vulnerable to zero-day exploits | Strong, patches applied systematically |

| Revenue Impact | Negative (lost sales, customer churn) | Neutral to Positive (stable, reliable service) |

A proactive plan transforms maintenance from a chaotic cost center into a predictable investment in operational stability.

The Financial Risk of Inaction

The global Software Support and Maintenance market is projected to reach USD 660.30 million by 2033, driven by increasing software complexity and the rising cost of failure.

For large enterprises, the financial exposure is acute. Unplanned downtime costs Global 2000 companies an estimated $1.4 trillion annually. Industrial manufacturers alone lose an estimated $50 billion per year to preventable disruptions. The data indicates a reactive strategy is financially unsustainable. More data is available on the growing maintenance market and its financial impact.

A software maintenance plan is not an IT expense to be minimized. It is a financial instrument for mitigating the cost of unplanned downtime and preserving operational stability.

Without a formal plan, maintenance becomes a cycle of emergencies. Ad-hoc fixes introduce new bugs and increase technical debt, which in turn cause the next failure, consuming more engineering hours. A structured plan is the only mechanism to break this cycle.

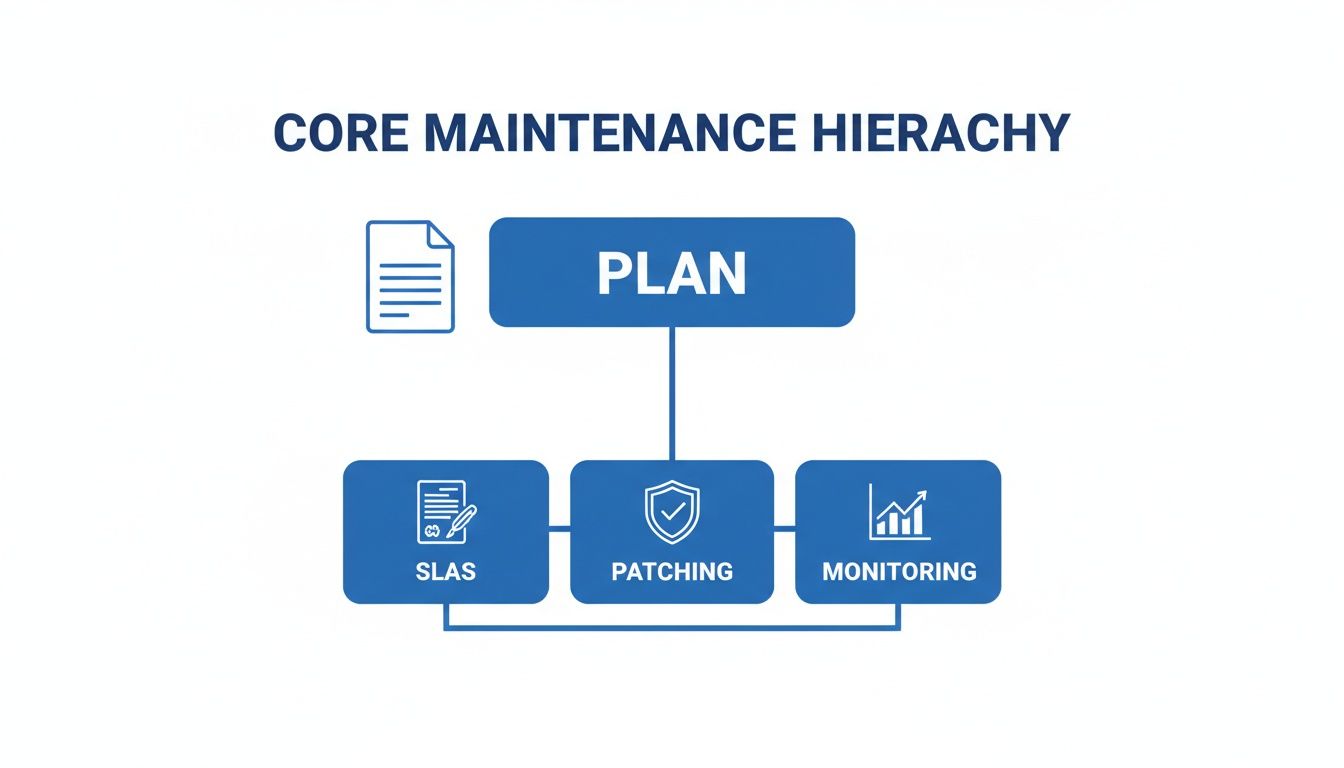

Breaking the Reactive Cycle

An effective maintenance plan forces a transition from chaos to control. It establishes a foundation for a stable, predictable system. These core components are not just “best practices”; they are essential pillars of risk management:

- Service Level Agreements (SLAs): Define uptime targets and response times, converting ambiguous goals like “maintain stability” into measurable, contractual commitments.

- Systematic Patching: A defined schedule for applying security patches and updates. This closes vulnerabilities before they can be exploited.

- Proactive Monitoring: Moves beyond binary “up/down” checks to track performance metrics and identify anomalies before they escalate to a full outage.

- Technical Debt Management: Formally allocates engineering capacity to refactor brittle code and remediate architectural weaknesses. It treats tech debt as a scheduled maintenance task, not an afterthought.

A structured plan provides the framework to stop the operational paralysis that affects many technical teams. It replaces reactive firefighting with proactive, predictable control.

The Core Components of an Effective Maintenance Plan

An effective software maintenance plan is not a high-level mission statement; it is a set of precise, interlocking commitments that create a framework for stability. Vague goals like “maximize uptime” should be replaced with concrete processes that specify team actions during an incident.

These components are designed to shift an organization from a reactive posture—where engineers are consumed by incidents—to a proactive one, where they prevent them. This is a fundamental change in how a business protects its operations and revenue.

Service Level Agreements: The Contractual Foundation

A Service Level Agreement (SLA) is the backbone of a maintenance plan. It is the contract that defines performance in measurable terms. Without an SLA, success is subjective, creating potential for disputes over whether a system is “stable enough.”

An effective SLA must go beyond a simple uptime percentage. Key metrics include:

- Mean Time To Recovery (MTTR): Measures the speed of incident resolution. For many users, recovery speed is more critical than uptime percentage.

- Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF): Measures system reliability between outages. Tracking MTBF helps identify systemic weaknesses before they become chronic issues.

- Error Budgets: A concept from Google’s Site Reliability Engineering (SRE) practice that defines an acceptable level of failure. It provides teams with a data-driven framework to balance innovation with core stability.

An SLA is not just a customer-facing promise; it is a tool for internal alignment. It forces difficult conversations about priorities and resources before a crisis, making it a critical risk management document.

A Clear Patching and Update Strategy

Neglecting software patches is a significant, unforced security error. A formal patching strategy is non-negotiable for maintaining security and stability. The primary decision is balancing the velocity of automated patching against the control of manual deployment for critical systems.

A robust strategy includes regular vulnerability scanning, a defined update schedule (e.g., “Patch Tuesday”), and a tested rollback plan in case a patch introduces regressions. Industry data shows 90% of mechanical failures are due to preventable issues; the same principle applies to software. Systematic patching eliminates a large category of self-inflicted outages.

System Monitoring and Proactive Alerting

Effective maintenance is about identifying problems before customers do. This requires moving beyond basic uptime checks to a more sophisticated approach that monitors for leading indicators of failure.

This means monitoring application performance metrics (APM), log data, and infrastructure health to detect anomalies that signal impending issues. A gradual increase in database query latency or a slow memory leak are classic early warnings of a potential outage. This proactive stance transforms monitoring from a reactive tool into a predictive one.

The Incident Response Protocol

During an incident, a pre-defined protocol separates a controlled response from organizational chaos. An incident response plan is a step-by-step playbook that dictates roles and actions during an outage, eliminating guesswork and ensuring a coordinated, efficient response.

A typical protocol includes these phases:

- Detection & Triage: Automated alerts notify the on-call engineer, who assesses business impact to set a severity level (e.g., P1 for a total outage, P3 for a minor bug).

- Communication: A designated incident commander provides clear status updates to internal stakeholders and, if necessary, customers.

- Resolution: The technical team works to identify the root cause and deploy a fix.

- Post-Mortem: A blameless review is conducted to analyze the incident’s root cause and implement preventive measures.

Scheduled Technical Debt Management

Technical debt is the implied cost of rework caused by choosing an easy (limited) solution now instead of using a better approach that would take longer. Left unmanaged, it compounds, making every future change slower, riskier, and more expensive.

A mature maintenance plan treats technical debt remediation as a scheduled activity. This typically means allocating a fixed percentage of each development cycle—often 15-20%—to refactoring brittle code, upgrading outdated libraries, and improving documentation. A plan is only as good as its documentation; exploring software documentation tools is a necessary step. By budgeting for this work, you prevent the systemic decay that often leads to major failures.

Moving Beyond Preventive: Why Predictive Maintenance Is the End Goal

Preventive maintenance is an improvement over reactive firefighting, but it is still fundamentally calendar-based. It assumes component failures follow a predictable schedule, which is rarely true for complex software systems. The most effective software maintenance plans are now shifting from preventive to predictive, using data to forecast failures before they occur.

This approach changes the operational model. Instead of patching a server every 30 days based on a schedule, you patch it when telemetry data indicates a specific vulnerability poses an active threat. It replaces schedule-based work with data-driven precision, focusing team capacity on mitigating actual risks.

The Technical Guts of Predictive Maintenance

Predictive maintenance is applied data science. It is built on collecting and analyzing large streams of operational data in real time. Cloud infrastructure provides the necessary compute power to process this information and execute machine learning (ML) models.

Core components include:

- Log Analysis: ML models can analyze millions of log entries to identify subtle patterns that precede a failure, such as a spike in a specific error message that indicates an imminent database connection pool exhaustion.

- Anomaly Detection: These algorithms establish a baseline of “normal” system behavior. They then flag any deviation—a slow memory leak, anomalous API response times—that a human operator would likely miss until a failure is already in progress.

- Historical Performance Data: By analyzing data from past incidents, models learn to identify leading indicators. If a CPU utilization of 80% for five minutes has preceded three of the last five outages, the system can learn to treat that pattern as a critical, pre-failure alert.

This is why robust monitoring is so critical. It is not just for dashboards; it is the foundation for collecting the data required to move from guessing to predicting.

As illustrated, monitoring is not just about observing current state. It is about building the historical record needed to forecast future failures.

From Cost Center to Strategic Advantage

The business case for predictive maintenance is strong. Market projections show the predictive maintenance software market growing from USD 10.6 billion to USD 47.8 billion by 2029. This growth is driven by real-world costs. Manufacturers, who lose an estimated $50 billion annually to unplanned downtime, have increased inquiries for these solutions by 275%. The data shows machine learning can extend asset life by an average of 30% by detecting faults earlier.

Predictive maintenance reframes the entire conversation. It transforms maintenance from a reactive cost center that drains resources into a strategic, proactive function that actively preserves revenue and enhances system reliability.

For a concrete example, consider predicting when a database connection pool will be exhausted. A model can analyze transaction volume, query latency, and active connection counts in real time. When it forecasts that the pool will be exhausted in the next 60 minutes, it can trigger an automated scaling event or alert an on-call engineer, preventing an outage.

This represents a shift from reactive support to proactive intelligence, a direction seen in tools like supportgpt. This is how maintenance evolves from a required chore into a competitive advantage, maintaining stability while competitors are still dealing with incidents.

Calculating the True Cost of Software Maintenance

Calculating the true cost of software maintenance is not as simple as reviewing a vendor’s quote. The actual figure is a function of your operational model, risk tolerance, and the system’s architectural complexity.

Miscalculating this number means your maintenance budget is likely to be rejected or prove insufficient during the first major incident.

A common rule of thumb is that annual software maintenance costs are 15-25% of the initial development cost. For a custom application with an initial build cost of $2 million, this translates to an annual budget of $300,000 to $500,000 for maintenance alone.

This figure often surprises stakeholders who view software as a one-time capital expense rather than a living asset requiring continuous investment. The 15-25% range is a baseline; legacy code, poor quality, and complex integrations can increase this figure significantly.

In-House vs. Outsourced Cost Models

The first major decision is whether to perform maintenance with an internal team or an external vendor. The cost structures are fundamentally different. An in-house team is a fixed cost (OpEx), while a vendor is typically a variable one.

An in-house team appears straightforward, but hidden costs can be substantial:

- Fully-Loaded Salaries: Base salary is only part of the cost. Benefits, taxes, and overhead typically add another 25-40%. A $150,000 engineer actually represents a business cost closer to $200,000.

- Tooling and Infrastructure: Licenses for monitoring, security scanning, and cloud environments are significant, recurring expenses.

- Training and Retention: Maintaining skills for legacy or specialized technology requires ongoing investment. Sourcing new expertise for technologies like COBOL can be difficult and expensive.

Outsourcing transfers these responsibilities but introduces different pricing models and potential risks.

Common Outsourced Pricing Structures

Maintenance vendors typically use one of several pricing models. Selecting the wrong model can lead to misaligned incentives and budget overruns.

Below is a breakdown of common cost models found in vendor proposals, with their respective advantages and disadvantages.

Software Maintenance Cost Model Comparison

| Cost Model | Typical Structure | Best For | Potential Pitfall |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed-Fee | A set monthly or annual price for a clearly defined scope of services (e.g., patching, monitoring). | Stable, predictable legacy systems with well-understood failure modes. | Scope creep. Any work outside the strictly defined agreement incurs additional charges, often at a premium. |

| Time & Materials (T&M) | You pay an hourly or daily rate for engineers’ time, plus the cost of any resources consumed. | Volatile systems where the required monthly effort is unknown. | Lack of cost control. Inefficient vendor teams can lead to significantly higher costs for the client. |

| Value-Based | The fee is tied to a specific business outcome, such as a percentage of revenue saved by preventing downtime. | Mission-critical applications where uptime has a direct, measurable monetary value. | Difficulty in defining and measuring “value.” Contracts can become complex and prone to disputes over KPI achievement. |

Choosing the correct model is critical. For most stable applications, a Fixed-Fee model offers predictability. For chaotic or rapidly evolving systems, T&M provides flexibility but demands rigorous oversight.

For highly specialized work, such as maintaining a legacy COBOL system, costs become even more specific. We see modernization projects intended to escape this maintenance trap priced in the $1.50-$4.00 per line of code range. This highlights the high cost of delaying maintenance. To better understand this, review our guide on calculating the real cost of technical debt.

Ultimately, the “true cost” must include the cost of inaction. If a $250,000 annual maintenance plan prevents a $1 million outage, it is not an expense; it is a high-return investment.

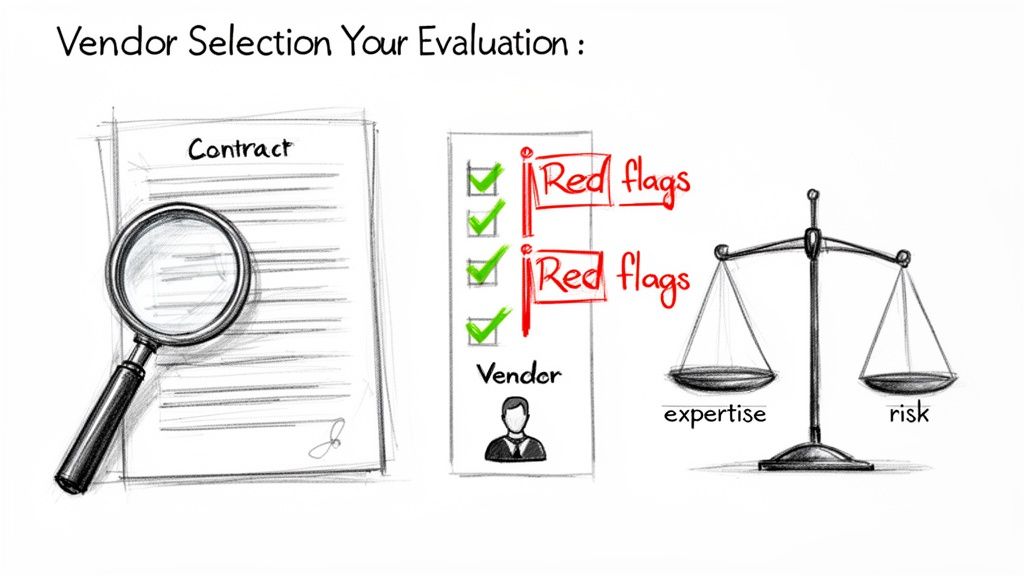

How to Select a Maintenance Vendor and Avoid Red Flags

Choosing a maintenance partner is a high-risk decision. An inadequate vendor doesn’t just underperform; they can introduce operational risk through incompetence, opaque processes, or misaligned incentives.

Most selection processes are flawed. They over-index on sales presentations and under-index on verifiable proof of competence. A polished presentation is irrelevant during a production database outage at 3 a.m.

The objective is to identify a partner who is technically proficient, operationally disciplined, and financially transparent. This requires a skeptical approach and a focus on questions that penetrate marketing claims.

Core Evaluation Criteria

Before reviewing pricing, you must validate a vendor’s core capabilities. A low-cost vendor who cannot execute a clean rollback or consistently fails to meet their SLA is not a bargain; they are a liability. Focus your evaluation on these non-negotiables.

-

Verifiable Technical Expertise: Do they have deep, demonstrated experience with your specific technology stack? Do not accept vague claims like “we are Java experts.” Request case studies on systems with similar architectural complexity. Insist on speaking with the senior engineers who would be assigned to your account, not just the sales team.

-

Incident Response Track Record: This is a key area of value. Request their documented incident response protocol. It should clearly define roles (e.g., Incident Commander), communication cadences, and escalation paths. Vague responses are a significant red flag.

-

Transparent Reporting: What specific metrics will they report on, and at what frequency? Expect detailed reports on SLA adherence (MTTR, MTBF), ticket resolution times, and patching compliance. Anything less allows them to obscure poor performance.

The most reliable predictor of future performance is past performance under pressure. A vendor’s reluctance to discuss a past failure in detail is more revealing than any glowing testimonial they provide.

Unmasking Common Vendor Red Flags

Underperforming vendors often use similar tactics. They target organizations seeking a quick solution that lack a structured vetting process. Identifying these tactics is the best defense against a poor long-term contract.

A comprehensive vendor evaluation is critical. For a deeper analysis, review our vendor due diligence checklist to ensure you are asking the right questions.

Probing Questions That Expose Weaknesses

Standard RFP questions elicit standard, pre-written answers. You must ask operational, scenario-based questions that reveal their actual thought process. Here are several examples:

-

“Describe a time a maintenance contract went poorly. What was the root cause, what specific steps did you take to remediate the situation with the client, and what internal processes did you change as a result?”

- Why it works: This question tests for honesty, accountability, and a commitment to process improvement. A vendor who blames the client or cannot articulate lessons learned is a significant risk.

-

“Walk me through your root cause analysis (RCA) process for a P1 incident. Who is involved, what artifacts are produced, and how do you ensure the recommended fixes are actually implemented?”

- Why it works: This reveals their operational maturity. A strong answer will mention blameless post-mortems, action items with owners and deadlines, and a feedback loop to prevent recurrence. A weak answer sounds like, “we have a call to figure it out.”

-

“Our SLA requires a 15-minute response time for critical incidents. What is your resource guarantee for ensuring an engineer with the correct skillset is available 24/7, and what are the financial penalties if you miss that target?”

- Why it works: This question addresses the contractual and financial realities of the software maintenance plan. It forces the vendor to move beyond vague promises to discuss specific staffing models, on-call rotations, and the financial penalties embedded in the SLA.

When to Keep Software Maintenance In-House

Outsourcing a software maintenance plan is not a universal solution. While access to specialized expertise can be valuable, transferring system control to a third party introduces its own risks. In some cases, keeping maintenance in-house is not about cost; it is a strategic decision to protect core business assets.

The assumption that outsourcing is always cheaper or more efficient is flawed. A third-party vendor’s incentives are not always aligned with your development velocity or intellectual property goals. This friction often becomes apparent long after a contract is signed and critical institutional knowledge has been transferred externally.

Protecting Core Intellectual Property

This is the primary reason to keep maintenance internal. When the software is the business—containing proprietary algorithms, unique business logic, or a data model that confers a competitive advantage—outsourcing creates a direct threat to your IP.

Regardless of the strength of the NDA, providing source code to a third party introduces an unavoidable risk of exposure. This is particularly true for vendors who serve multiple clients, some of whom may be direct competitors.

The moment your core IP is documented in a vendor’s ticketing system, it is no longer secure. For proprietary systems, the risk of an intellectual property leak almost always outweighs the potential cost savings from outsourcing.

Managing Highly Specialized or Proprietary Technology

Vendors are most efficient when working with standardized technologies. Their business model depends on repeatable processes and a pool of engineers who can service multiple clients using a common playbook. If your technology stack is highly customized or proprietary, finding a vendor with genuine expertise is difficult and expensive.

In these situations, you will likely pay a premium for the vendor to learn your system. Their learning curve becomes your operational risk. Your internal team, who built and evolved the system, possesses institutional knowledge that is nearly impossible and certainly not cost-effective to transfer.

Supporting Rapid Iterative Development

Outsourcing maintenance creates a rigid separation between development and operations. For teams practicing Agile or DevOps, where the build-release-maintain cycle is continuous, this separation creates significant friction.

The communication overhead of managing an external team—creating tickets, awaiting responses, scheduling calls—is fundamentally incompatible with rapid iteration. This friction can slow the entire development lifecycle. When your own developers can rapidly diagnose and resolve a production issue, it bypasses the entire vendor management process. An integrated maintenance plan is simply faster.

Your Questions, Answered

Even a well-structured plan will encounter practical challenges. Here are answers to common questions from leaders implementing a formal maintenance operation.

We Have a Huge, Old System. Where Do We Even Start?

The first step is not to write code. It is to conduct a comprehensive system audit. You must establish a baseline before you can plan improvements.

This involves more than a code review. It requires historical analysis—interviewing previous developers, mapping all system integrations, and creating a risk register. The audit output becomes your strategic plan, identifying which components are most likely to fail and what a realistic SLA should be. Without this data, your maintenance plan is based on guesswork.

How Do I Get the CFO to Approve a Budget for Proactive Work?

You must frame the request in terms of financial risk, not technical debt. Leadership is less likely to approve vague requests to “refactor code” and more likely to approve plans that prevent revenue loss.

Do not ask for time to fix code. Present a business case that quantifies the cost of inaction. Tie every requested dollar directly to a reduction in expensive downtime, emergency support costs, and customer churn.

For example, instead of saying, “We need to update our database drivers,” frame the request as: “Our system experienced three outages last quarter due to outdated drivers, resulting in an estimated $250,000 in lost sales and support costs. A six-week project to upgrade them will cost $90,000 and is projected to eliminate 80% of these specific failures.”

What’s the Real Difference Between a Maintenance Plan and an SLA?

Understanding this distinction is critical because it separates the work from the promise.

The software maintenance plan is the comprehensive strategy—the “what” and the “how.” It is the operational playbook that covers everything from patching schedules and monitoring configurations to incident response protocols.

The SLA (Service Level Agreement) is a specific, measurable commitment within that plan. It’s the “when” and “how fast.” It defines the contractual targets you are committing to, such as 99.9% uptime or a 15-minute response time for critical incidents. The maintenance plan is the sum of all the work you do to meet the promises defined in the SLA.

Making defensible decisions about software maintenance and modernization requires unbiased data. Modernization Intel provides market intelligence on 200+ implementation partners, including real cost data, documented failure points, and verified specializations, helping you select the right vendor without the sales pitch. Get your vendor shortlist at https://softwaremodernizationservices.com.

Need help with your modernization project?

Get matched with vetted specialists who can help you modernize your APIs, migrate to Kubernetes, or transform legacy systems.

Browse Services